Capital Allocation and Liquidity Management for Digital Health Angel Investors

Disclaimer: The thoughts and opinions expressed in this essay are my own and do not reflect the views of my employer, Datavant.

Abstract

Digital health angel investing presents unique liquidity challenges that require thoughtful capital allocation strategies. This essay examines practical frameworks for determining appropriate investment amounts based on net worth, income, and existing portfolio composition. Key considerations include:

• The extended timeline for healthcare exits (typically 8-12 years versus 5-7 years in consumer tech)

• Reserve requirements for follow-on investments across multiple funding rounds

• The compounding effect of deploying capital across multiple vintage years

• Income-based allocation strategies for high-earning professionals versus net worth-based approaches for established wealth

• Recommended allocation ranges of 5-10% of investable assets for experienced investors and 2-5% for beginners

• The importance of maintaining 2-3x capital reserves beyond initial check sizes

• Portfolio construction targets of 15-25 companies for adequate diversification

The essay provides detailed mathematical examples and cash flow scenarios to help investors avoid the common trap of overcommitting capital early and finding themselves unable to support existing portfolio companies in later rounds.

The question of how much capital to allocate to angel investing in digital health is one that prospective investors wrestle with constantly, and frankly it is a question that does not get enough serious treatment in the literature. Most advice on angel investing comes from the broader tech world where exit timelines are shorter and the sector dynamics are fundamentally different from healthcare. The reality is that healthcare investing demands a much more conservative and thoughtful approach to capital allocation precisely because the illiquidity period tends to be substantially longer and the capital intensity of healthcare companies often requires more follow-on support than your typical SaaS business.

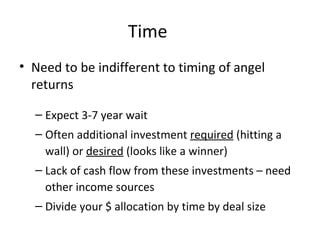

Let me start with the uncomfortable truth that most new angel investors do not want to hear. If you are going to do this seriously and build a portfolio that has a reasonable shot at generating venture-scale returns, you need to be prepared to have your capital locked up for a decade or more. The median time to exit for a successful digital health company is somewhere between eight and twelve years from founding, and if you are investing at the seed stage, you are probably looking at the longer end of that range. This is not consumer internet in 2012 where companies could go from zero to acquisition in three years. Healthcare has regulatory complexity, sales cycles that involve navigating byzantine procurement processes, clinical validation requirements, and integration challenges that simply take time to work through. The companies that succeed are typically the ones that methodically execute over long time horizons, not the ones that try to blitz scale.

This extended timeline has profound implications for how you should think about allocation. The first and most important principle is that you should only invest capital that you genuinely do not need for at least ten years. Not five years where you might want to buy a house. Not seven years when your kid is heading to college. Ten years minimum, and ideally longer. If there is any scenario in which you might need to liquidate your angel investments to cover living expenses or other financial obligations within that timeframe, you are taking on unacceptable risk. Angel investments in early stage companies have essentially zero liquidity until an exit event occurs. There are secondary markets, but they are inefficient, opaque, and typically only available for companies that are already on strong trajectories toward exit. For most of your portfolio companies, there will be no realistic way to get your money out until they either get acquired or go public, and the probability of either outcome is quite low for any individual company.

The traditional allocation frameworks that come out of the venture world typically suggest that angel investors allocate somewhere between five and fifteen percent of their investable assets to angel investing. This range makes sense as a starting point, but it needs to be contextualized based on your specific financial situation, your income profile, and your investment objectives. The mechanics of how you calculate this allocation matter quite a bit, and there are really two different approaches depending on whether you are investing primarily from accumulated wealth or from ongoing income generation.

For investors who have already accumulated significant wealth and are thinking about angel investing as one component of a diversified portfolio, the net worth based approach makes the most sense. In this framework, you start by calculating your total investable assets, which excludes your primary residence, any illiquid assets like private business interests that are not related to your angel investing, and any capital that is earmarked for near term needs. Take whatever number you come up with and multiply it by something in the range of five to ten percent. That is your total angel investing budget over the lifetime of your angel investing career, not per year. This is a critical distinction that trips up a lot of new investors. If you have two million in investable assets and decide to allocate ten percent to angel investing, you have two hundred thousand dollars total to deploy, not two hundred thousand per year.

Within that total budget, you then need to think about deployment pace and portfolio construction. The conventional wisdom is that you need at least fifteen to twenty companies in your portfolio to have a reasonable shot at capturing one or two big winners that will drive the majority of your returns. This is just power law math. In venture, the top ten percent of investments typically generate more than one hundred percent of the returns, and the top one percent generate outsized multiples that can return an entire fund. If you only invest in five companies, the probability that one of them ends up in that top decile is pretty low. At twenty companies, your odds improve considerably.

So if you have two hundred thousand to deploy and you need to build a portfolio of at least fifteen companies, you are looking at initial check sizes of somewhere around ten to fifteen thousand per company. This immediately creates a problem though, because at the seed stage in digital health, companies are typically raising rounds of one to three million dollars, and a ten thousand dollar check represents a pretty small ownership stake. More importantly, you need to reserve capital for follow-on investments in your winners. The companies that are successful will almost certainly raise Series A, Series B, and potentially Series C rounds before they exit, and you want to be able to participate in those rounds to avoid getting diluted out of meaningful ownership.

The conventional wisdom in venture is to reserve two to three times your initial check size for follow-on investments. So if you write a ten thousand dollar initial check, you should plan to have another twenty to thirty thousand available to invest in that company over time. This is where the math starts to get really constraining. If you are building a portfolio of twenty companies with ten thousand dollar initial checks, you are deploying two hundred thousand in initial capital. But if you need to reserve two to three times that amount for follow-ons, you actually need four hundred to six hundred thousand in total capital to properly support the portfolio. This is the point where a lot of new angels realize they have significantly underestimated the capital requirements.

The alternative approach is to deploy capital more slowly over time and build your portfolio over multiple vintage years. Instead of trying to write twenty checks in your first year, you might write five to seven checks per year and build up to a portfolio of twenty companies over three to four years. This has the advantage of spreading out your capital deployment and reducing the immediate cash requirement, but it also means that your portfolio construction takes much longer and you have less diversification in the early years. The other challenge with this approach is that market conditions change, and if you happen to start investing right before a correction or a shift in the fundraising environment, you might find that the deal flow quality changes or that pricing dynamics shift in ways that affect your entire cohort.

For investors who are deploying capital primarily from ongoing income rather than accumulated wealth, the income based allocation approach often makes more sense. This is particularly relevant for high earning professionals like physicians, executives at healthcare companies, or successful entrepreneurs who are generating significant annual income but have not yet accumulated substantial liquid wealth. In this model, you might allocate something like five to fifteen percent of your annual after-tax income to angel investing each year. So if you are making five hundred thousand per year after taxes and you allocate ten percent, that is fifty thousand per year that you can deploy into your angel portfolio.

The advantage of the income based approach is that it aligns your investment pace with your ability to generate new capital, which reduces the risk of overcommitting early and finding yourself unable to support your portfolio companies later. The disadvantage is that it requires discipline and consistency over multiple years to build a meaningful portfolio, and it can be challenging to maintain that discipline when market conditions shift or when you have other competing financial priorities. The other consideration is that this approach tends to result in smaller check sizes unless you are generating very high income, which can make it harder to get into competitive deals or to secure meaningful ownership stakes.

Regardless of which approach you take, one of the most important principles is to maintain significant reserve capital beyond what you deploy initially. This is not just about having money available for follow-on investments, it is about having the optionality to double down on your winners and to avoid being a forced seller in down markets. The venture funding environment is cyclical, and there will inevitably be periods where capital is scarce and where your portfolio companies struggle to raise their next rounds. Having reserve capital available during those periods gives you the ability to support your best companies through difficult times and potentially increase your ownership at attractive valuations.

The mechanics of how you manage these reserves matters quite a bit. Some angels keep their reserve capital in cash or short term treasuries so that it is immediately available when needed. Others keep it invested in liquid securities and plan to liquidate as needed when follow-on opportunities arise. The challenge with the latter approach is that it introduces timing risk. If the public markets are down at the same time that your portfolio companies are raising new rounds, you might find yourself needing to sell liquid holdings at depressed prices to fund your follow-on investments. This is obviously not ideal and can create a negative compounding effect on your overall portfolio returns.

There is also the question of how to think about the opportunity cost of holding large reserve balances. If you are keeping two hundred thousand in cash to fund potential follow-on investments over the next three to five years, that capital is earning essentially nothing in real terms after inflation. The alternative is to keep that capital invested and accept some liquidity risk, but this requires careful planning and a realistic assessment of how quickly you might need to access the funds. In practice, most experienced angels end up with a hybrid approach where they keep some portion of their reserves in cash for immediate deployment and the rest in liquid securities that can be accessed on a slightly longer timeline.

The compounding effect of deploying capital across multiple vintage years is something that does not get enough attention in discussions about angel allocation. When you start angel investing, you are essentially initiating a capital deployment cycle that will require ongoing funding for many years even if you never make another initial investment. Let me walk through a concrete example to illustrate this. Suppose you start in year one and make five initial investments of ten thousand each, for a total deployment of fifty thousand. You reserve another one hundred thousand for follow-on investments across these five companies.

In year two, three of your five companies raise Series A rounds and you decide to invest another ten thousand in each of them. That is another thirty thousand deployed, leaving you with seventy thousand in reserves. You also make another five initial investments, deploying another fifty thousand in new companies and reserving another one hundred thousand for their follow-ons. At this point, you have committed two hundred and thirty thousand in total and you have ten companies in your portfolio.

By year three, things start to get complicated. Some of your year one companies are raising Series B rounds. Some of your year two companies are raising Series A rounds. You also want to make new initial investments to continue building your portfolio. The capital requirements start to compound because you are simultaneously supporting existing portfolio companies across multiple funding stages while also trying to add new companies. This is the point where a lot of angels realize they have overextended themselves and they have to start making difficult triage decisions about which companies to support.

The way to avoid this trap is to be very conservative in your initial deployment and to maintain discipline about your portfolio size. If you are only making five initial investments per year and you are being selective about which follow-on opportunities you participate in, you can probably sustain this with annual deployment of fifty to one hundred thousand depending on how your companies are performing. But if you are trying to make ten or fifteen initial investments per year, the capital requirements very quickly become unsustainable unless you have very deep pockets.

Portfolio construction requirements in healthcare angel investing are somewhat different from other sectors because of the heterogeneity of business models and regulatory pathways within digital health. A well diversified healthcare angel portfolio should include exposure to different segments like provider workflow tools, patient engagement platforms, payment and financing solutions, clinical decision support, care delivery models, and data infrastructure. Each of these segments has different capital intensity requirements, different go-to-market motions, different regulatory considerations, and different exit profiles. By diversifying across segments, you reduce your exposure to sector specific risks like regulatory changes that might disproportionately impact one category of companies.

The challenge is that achieving this level of diversification requires a larger number of investments than you might need in a more homogeneous sector. If you are only investing in consumer internet companies, fifteen to twenty investments might give you adequate diversification. In healthcare, you probably need at least twenty to twenty five investments to get meaningful exposure across the different segments, and ideally you would have multiple investments in each segment so that you are not overly dependent on any single company. This obviously increases the total capital requirement and makes portfolio construction take longer.

Another consideration that is specific to healthcare is the importance of having exposure to companies at different stages of regulatory maturity. Some companies will have clear pathways to market and minimal regulatory risk. Others will be navigating complex FDA approval processes or will be dependent on CMS reimbursement decisions. Having a mix of both types in your portfolio is important because it gives you both near term shots on goal with the less regulated companies and longer term optionality with the companies that are building more defensible moats through regulatory approvals. But again, this requires a larger portfolio and more capital to achieve the right balance.

Cash flow planning is one of the most overlooked aspects of angel allocation strategy. When you make an angel investment, you are not just committing that initial check, you are also committing to a multi-year cash flow obligation that could potentially require you to deploy significant additional capital at uncertain points in the future. The timing of these follow-on investments is largely outside of your control because it depends on when your portfolio companies raise their next rounds, and the amounts required can vary significantly based on the terms of those rounds and how much ownership you are trying to maintain.

This creates a planning challenge because you need to maintain liquidity to fund these obligations without knowing exactly when they will come due or how large they will be. The companies that are doing well will likely raise new rounds on relatively predictable timelines, perhaps every eighteen to twenty four months. But the companies that are struggling might go longer between rounds, or they might raise bridge rounds at inopportune times when you have limited capital available. The companies that are doing exceptionally well might raise at much higher valuations where your pro rata rights are expensive to exercise relative to the ownership you maintain.

In practice, most angels end up with a portfolio where about thirty to forty percent of their companies raise follow-on rounds in any given year. So if you have twenty companies in your portfolio, you might have six to eight companies raising new rounds each year. If your target follow-on investment is ten to fifteen thousand per round, you are looking at sixty to one hundred and twenty thousand in annual follow-on deployment once your portfolio is mature. This is on top of any new initial investments you are making, which means your total annual deployment requirement could easily be one hundred to two hundred thousand if you are actively building your portfolio while also supporting existing companies.

The exit timeline expectations for digital health companies are critically important for allocation planning because they determine how long your capital will actually be tied up. The data here is pretty clear that healthcare exits take longer than other sectors. If you look at companies that went public or got acquired in the last five years, the median time from founding to exit for digital health companies is somewhere around nine to ten years. For comparison, enterprise SaaS companies typically exit in six to eight years, and consumer internet companies can exit in four to six years if they are successful.

This longer timeline is driven by several factors that are structural to healthcare and are unlikely to change. First, healthcare sales cycles are just longer because of the complexity of the buying process and the number of stakeholders involved in purchasing decisions. A typical healthcare system might take twelve to eighteen months to evaluate, pilot, and fully implement a new solution, and companies need to sign multiple customers before they have the scale and predictability required for an exit. Second, clinical validation requirements mean that companies often need to demonstrate outcomes over multiple years before they can command premium valuations. Third, regulatory approvals and reimbursement decisions add time to the commercialization pathway for many companies. And fourth, the acquirer base in healthcare is more conservative and more focused on proven revenue than in other sectors, which means companies need to demonstrate more traction before they become attractive acquisition targets.

For angel investors, this means you need to be planning for your capital to be locked up for at least a decade and potentially longer. The companies you invest in this year might not exit until the mid two thousand thirties, which sounds absurd until you actually do the math and realize that a company founded in twenty twenty five and taking ten years to exit would exit in twenty thirty five. This is not some distant hypothetical future, this is just the reality of the timeline you are signing up for.

The implications for allocation are significant. If you are investing capital that you might need in five years, you are taking on enormous liquidity risk. If you are investing capital that you know you will not need for fifteen years, you have much more flexibility to be patient and to let your companies mature. This is why the age and life stage of the angel investor matters so much. A thirty five year old investor with a long earning runway ahead of them can afford to be much more aggressive with their allocation than a sixty year old investor who might need to access their capital for retirement in the next ten to fifteen years.

The most common allocation mistakes I see from new digital health angels fall into a few predictable categories. The first is investing too much too quickly without understanding the follow-on capital requirements. New angels get excited, they see a few companies they love, they write five or six checks in their first year, and then they realize they have deployed most of their capital and they have no reserves left for follow-ons. When their best companies raise Series A rounds eighteen months later, they are forced to let their ownership get diluted because they do not have the capital to participate. This is incredibly frustrating and completely avoidable with proper planning.

The second mistake is underestimating the total capital requirement for building a diversified portfolio. New angels hear that they need twenty companies in their portfolio and they think they can do that with one hundred thousand dollars. The math does not work unless you are writing five thousand dollar checks, and at that check size you are probably not getting into the best deals and you are definitely not going to have meaningful ownership in your winners. The reality is that building a proper angel portfolio in digital health probably requires three hundred to five hundred thousand in total capital if you are being realistic about check sizes and reserve requirements.

The third mistake is not thinking carefully enough about the timeline and the compounding nature of capital deployment. Angels assume they can front load their investments, build their portfolio quickly, and then just maintain it with occasional follow-ons. But the actual capital requirement peaks several years into your angel investing journey when you are simultaneously supporting multiple cohorts of companies at different stages. If you do not plan for this, you end up in a position where you are capital constrained at exactly the wrong time.

The fourth mistake is failing to maintain adequate liquidity outside of the angel portfolio. Angel investing should be a small part of your overall wealth management strategy, not the dominant piece. You need to have adequate liquid reserves for living expenses, for emergencies, and for other investment opportunities that might arise. If you put too much of your net worth into illiquid angel investments, you create enormous stress and you might be forced to make suboptimal financial decisions in other parts of your life.

A practical framework that I think works well for most new digital health angels is to start with a very conservative allocation and then scale up over time as you build experience and as your financial situation allows. In your first year, consider making just three to five investments with check sizes of ten to fifteen thousand each. Reserve two to three times that amount for follow-ons. This gives you a total first year commitment of one hundred and fifty to three hundred thousand, which is manageable for most accredited investors who are serious about angel investing.

Use that first year to learn the market, to build relationships with other investors, to develop your diligence process, and to figure out what types of companies and founders you want to back. In year two, if you enjoyed the experience and if your financial situation supports it, you can scale up to five to seven new investments while also participating in follow-on rounds for your year one companies. By year three and four, you should have a clearer sense of what level of annual deployment is sustainable for you and you can settle into a steady state pace.

This measured approach has several advantages. It limits your downside risk if you discover that angel investing is not a good fit for your personality or if your financial circumstances change. It gives you time to learn and to make inevitable mistakes with smaller amounts of capital. It allows you to build relationships in the ecosystem before you are trying to deploy large amounts of capital. And it creates a more predictable and manageable cash flow profile that is easier to sustain over the long term.

The reality is that angel investing in digital health is not for everyone, and it is certainly not something you should do with capital you cannot afford to lose or to have locked up for a very long time. But for investors who have the financial capacity, who have the patience for long holding periods, who enjoy working with early stage companies, and who want exposure to the innovation happening in healthcare technology, it can be an incredibly rewarding way to deploy capital. The key is to approach it thoughtfully, to be realistic about the capital requirements and timelines, and to maintain discipline about your allocation strategy so that you do not overextend yourself. Healthcare is a sector where patience and persistence are rewarded, and the same principles apply to angel investing in the space.

If you are interested in joining my generalist healthcare angel syndicate, reach out to treyrawles@gmail.com or send me a DM. We don’t take a carry and defer annual fees for six months so investors can decide if they see value before joining officially. Accredited investors only.