Comparing PE Fund Returns: Physician Practice Roll-ups vs. Pure Play Mid-Market Health Tech

Private equity (PE) funds have long targeted inefficiencies and fragmentation in healthcare as a vector for value creation. Two prominent strategies have emerged in the last decade: (1) the consolidation of physician practices through roll-up models, and (2) investment in pure play middle-market health technology companies. While both offer compelling entry points, they differ substantially in their return profiles, capital intensity, risk structures, and exit dynamics. This essay analyzes the comparative return characteristics of each strategy from the lens of PE fund economics, underlying operational complexity, and structural tailwinds or headwinds across market cycles.

1. Return Profiles and IRR Expectations

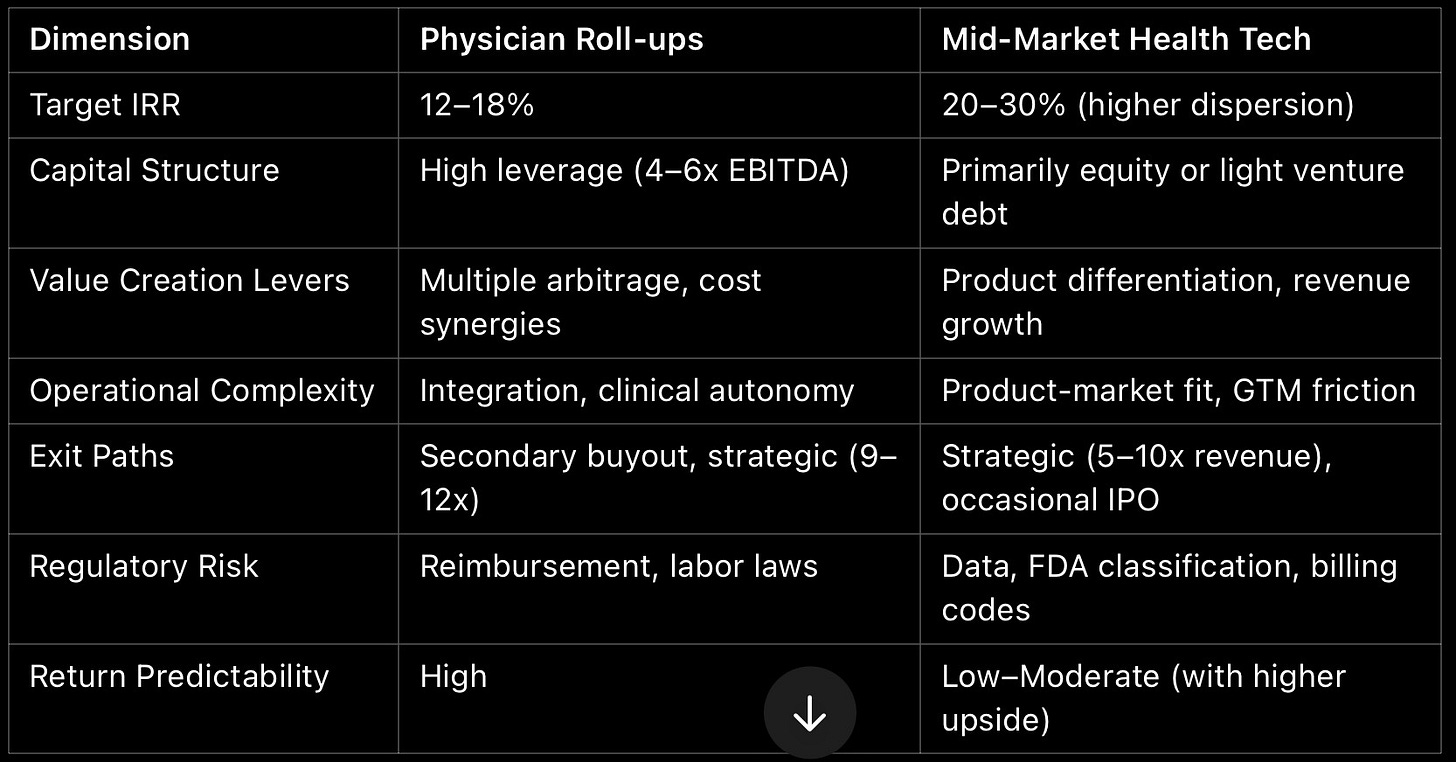

PE funds executing physician practice roll-ups typically target low double-digit IRRs (12–18%) with an emphasis on multiple arbitrage and operational leverage. Conversely, funds investing in pure play mid-market health tech—especially SaaS or platform-based models—often aim for higher IRRs (20–30%), particularly when backing early growth-stage or scaled Series B/C companies that have room to expand EBITDA multiples.

The delta in expected returns is primarily driven by the nature of value creation:

Roll-ups monetize fragmented markets and standardize administrative operations (e.g., billing, compliance, EMRs), often realizing value through scale and arbitrage.

Health tech investments create value through product differentiation, IP moats, recurring revenue, and platform extensibility (e.g., modular APIs, data liquidity).

However, the IRR dispersion in health tech is wider. Top quartile funds can deliver 3–5x MOICs, but capital is at significantly higher risk due to technology obsolescence, prolonged sales cycles (especially in provider and payer markets), and regulatory risk tied to data use (HIPAA, 21st Century Cures, ONC regulations). Physician practice roll-ups offer tighter return bands, albeit lower upside ceilings.

2. Capital Structure and Debt Utilization

Roll-up strategies are significantly more levered. Physician practice platforms frequently employ 4–6x EBITDA in debt, capitalizing on stable cash flows from fee-for-service and value-based care contracts. These cash flows, typically underpinned by Medicare or commercial insurance, are deemed reliable enough for aggressive leverage. Platforms in dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology, for example, often exhibit low cyclicality, which supports a traditional LBO model.

Health tech companies, particularly those in growth stages, are capitalized more conservatively. Many lack EBITDA altogether or reinvest profits into R&D, engineering, or go-to-market functions. Debt, when used, is often venture debt or structured as non-dilutive growth capital. As a result, equity is the primary vehicle for value appreciation, and returns hinge on multiple expansion and revenue growth, not financial engineering.

The implication for PE fund returns is critical: leverage magnifies returns in physician roll-ups but introduces refinancing and integration risk. Health tech relies on executional alpha, requiring domain expertise and strategic patience to weather long implementation cycles in clinical or enterprise settings.

3. Operational Complexity and Platform Risk

Operational risk in physician practice roll-ups is centered around integration and clinical autonomy. Cultural misalignment, EHR standardization, and variable payer mix across geographies can erode margin assumptions. In addition, physician turnover—especially of founding or high-volume providers—can materially impact revenue. This places a premium on human capital retention strategies, post-close governance, and clinical operations playbooks.

In contrast, mid-market health tech investments must navigate product-market fit risk, GTM friction (especially in selling to IDNs or payers), and evolving reimbursement models (e.g., CPT codes for remote monitoring or digital therapeutics). While scaling a SaaS platform can lead to superior gross margins (often >70%), getting past pilots and into multi-year enterprise contracts can take 18–24 months, complicating underwriting models.

Operational alpha in health tech lies in engineering velocity, clinical validation (often requiring RWE or peer-reviewed evidence), and regulatory navigation—very different skill sets than revenue cycle optimization or physician recruitment.

4. Exit Dynamics and Strategic Buyer Appetite

Physician roll-ups are typically exited to larger PE funds or to strategic consolidators looking for market share and network density (e.g., Optum, CVS, or private insurers acquiring primary care assets). These exits tend to transact at 9–12x trailing EBITDA, assuming successful integration and stable clinician rosters.

Health tech exits, by contrast, are more diverse but more volatile. Strategic acquirers (e.g., Cerner, Oracle Health, UnitedHealth Group, or Teladoc) may pay 5–10x revenue for category-leading platforms, but timing and valuation are heavily influenced by macro conditions (interest rates, public market multiples, SPAC reversals, etc.). IPOs are rarer post-2021, so many mid-market platforms aim to become acquisition targets once they demonstrate enterprise scalability and recurring revenue north of $30M ARR.

From a fund return perspective, this means physician roll-ups offer predictability and linearity, while health tech can deliver asymmetric upside but is more correlated to timing risk and macro conditions.

5. Regulatory and Reimbursement Risk

Physician roll-ups are more exposed to reimbursement compression and policy shifts (e.g., changes in Medicare fee schedules, site-neutral payments). Additionally, PE ownership of practices has drawn scrutiny from policymakers and payers concerned about cost inflation and overutilization.

Health tech is more insulated from direct reimbursement risk but faces its own regulatory gauntlet: ONC interoperability mandates, FTC scrutiny over data privacy, and FDA classification (for software-as-a-medical-device). Companies in the RPM or digital therapeutics space may find themselves dependent on code coverage, which varies widely across commercial payers.

In short, while both strategies are regulated, the vectors of risk differ: roll-ups are exposed to pricing pressure and physician labor dynamics; health tech faces regulatory ambiguity and misaligned incentives in adoption.

Conclusion: Comparative Summary

For PE funds, the choice between physician roll-ups and mid-market health tech hinges on risk appetite, time horizon, and operational expertise. Roll-ups provide repeatable, cash-yielding models with moderate upside, while health tech offers higher risk-adjusted returns that demand deep sector fluency and strong value creation capabilities. An optimal healthcare portfolio strategy likely includes both: roll-ups for base case defensibility and health tech for asymmetric upside.