Speculative Futures: Health Insurance as Outlier Protection and the Evolution of Healthcare Economics

In healthcare, insurance has evolved from a risk management tool into a prepayment system for routine, predictable medical expenses. This structural inversion of insurance principles has contributed to spiraling healthcare costs, rampant administrative complexity, and opaque pricing structures. Yet, an intriguing counterfactual emerges when one considers an alternative model: a healthcare financing system where health insurance is reserved strictly for statistically rare, high-cost events, and routine expenses—low-cost drugs, minor procedures, preventive care—are paid for directly by individuals or through specialized savings vehicles. Speculating on this transformation reveals a landscape replete with both opportunity and complexity, especially when considering how private industry and public sector innovation initiatives might pilot and evaluate such a paradigm shift.

In envisioning this alternative healthcare financing future, one must start with the core distinction between risk pooling and cost sharing. Traditional insurance markets, whether property and casualty or life insurance, function by pooling unpredictable and rare catastrophic risks across a broad population. Healthcare, however, blurs this distinction; predictable and inevitable expenses—annual physicals, maintenance medications—are incorporated into insurance products, transforming them into inefficient prepayment vehicles. A future model emphasizing pure risk pooling would relegate insurance strictly to outlier events: hospitalizations exceeding specific thresholds, oncology treatments, organ transplants, intensive trauma care. All other transactions would be consumer-driven and cash-priced, often through mechanisms like Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) or subscription-based primary care.

Testing this future requires robust experimentation, particularly within the complex regulatory framework that defines American healthcare. Private industry holds several potential levers for such experiments. Self-insured employers, under ERISA exemptions, enjoy latitude to design health benefits outside of fully insured market constraints. Large employers could pioneer models where employees are provided catastrophic insurance plans with high attachment points—say $10,000 or $20,000—and a concurrent annual cash stipend deposited into an HSA-like vehicle for routine care. These models would enable direct observation of consumer healthcare purchasing behavior when individuals are spending their own money below the catastrophic threshold. Actuarial analysis could then focus on the frequency and severity of high-cost claims relative to the cost of fully insured comprehensive plans, comparing outcomes longitudinally across demographic and morbidity strata.

Another vector for private sector innovation would involve the insurance industry itself. A regulatory framework that explicitly allows insurers to market outlier-only products—catastrophic coverage stripped of mandated first-dollar services—could foster an actuarial reengineering of health risk products. Insurers could stratify cohorts based on historical cost data, isolating truly unpredictable events, and pricing policies accordingly. Testing these products would require relaxation of essential health benefit mandates under the Affordable Care Act, suggesting a need for legislative or regulatory carve-outs, potentially at the state level under Section 1332 State Innovation Waivers. States interested in healthcare reform experimentation, such as Utah, Colorado, or Arkansas, might be fertile grounds for such pilots. Through waivers, states could approve insurance products offering exclusively catastrophic coverage, combined with mandatory HSAs or direct primary care memberships, providing an empirical basis for longitudinal evaluation of utilization patterns, financial sustainability, and clinical outcomes.

Public sector innovation would be equally critical. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), through its Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), could sponsor demonstration projects specifically designed to evaluate the impact of catastrophic-only insurance models. These projects could target Medicaid expansion populations or dual eligibles with high variability in healthcare needs, offering catastrophic coverage with structured cash transfers for routine expenses. CMMI’s statutory authority allows it to waive normal Medicare and Medicaid requirements in pursuit of cost reduction and quality improvement, providing a regulatory vehicle for real-world testing. Such pilots would necessitate sophisticated longitudinal data collection, capturing not only costs and utilization but clinical outcomes, social determinants of health, and patient satisfaction metrics.

To ensure rigorous evaluation, regulation would need to mandate robust data collection standards. Private and public insurers alike would be required to submit de-identified longitudinal claims, encounter, and outcome data to central research repositories. Data would need to be structured to distinguish between expenditures on routine care and catastrophic care, enabling analysis of shifts in spending patterns, delays in necessary care, and the net impact on morbidity and mortality. The adoption of common data models, such as OMOP CDM (Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model), would facilitate cross-payer analyses. Furthermore, outcome measures would need to expand beyond traditional HEDIS metrics to include patient-reported outcomes, functional status measures, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), enabling comprehensive value assessments.

The actuarial challenges of modeling such systems should not be underestimated. Traditional healthcare actuarial science focuses heavily on predicting average per member per month (PMPM) expenditures across comprehensive coverage products. A catastrophic-only model would instead require a rare event modeling approach, analogous to that used in property catastrophe reinsurance markets. Extreme value theory, tail risk modeling, and stochastic simulation techniques would become central to health actuarial work. Actuaries would need to develop new credibility formulas based on high-cost claim occurrence frequencies rather than broad population averages. Regulators would need to update actuarial opinion and certification standards accordingly, ensuring solvency protections while accommodating innovative product designs.

In parallel, state insurance regulators would play a vital role in overseeing the rollout of outlier-only insurance pilots. Traditional minimum loss ratio (MLR) rules, which require insurers to spend a fixed percentage of premiums on clinical care, would need to be rethought. MLRs, designed for comprehensive insurance, become less meaningful when products are aimed solely at rare, high-cost events. Regulators might instead impose solvency standards focused on catastrophic risk reserves, much like surplus requirements in other lines of insurance. Transparent rate filing requirements would also be critical, ensuring that insurers cannot exploit consumer information asymmetries in a market where upfront pricing becomes paramount.

Beyond insurance and provider market dynamics, pharmaceutical supply chains would undergo profound transformations in a world where low-cost drug purchases are direct consumer transactions. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), whose business models center on opaque rebate arrangements and formulary control, would see their leverage evaporate. Transparent cash pricing of generics would become the norm, with competitive forces driving down prices for most maintenance medications. Specialty drugs, representing a disproportionate share of high-cost claims, would remain within the catastrophic insurance layer, necessitating new pricing and access models. Here again, regulatory innovation could facilitate experimentation: for instance, allowing states to create public pharmaceutical purchasing cooperatives designed to negotiate directly with manufacturers for catastrophic tier drugs, bypassing traditional PBM structures.

Testing the impact of this future state also requires attention to behavioral economics. Transitioning from first-dollar insurance coverage to a consumer-driven model introduces the risk of underutilization, especially for preventive services with positive externalities. Pilot programs would need to incorporate behavioral interventions, such as default enrollment into low-cost preventive care bundles or gamified incentives for annual screenings, to ensure that individuals continue to engage with necessary healthcare services. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) embedded within pilot programs could evaluate the efficacy of these interventions, informing broader policy decisions about how to design a consumer-driven system that maintains public health gains.

The broader macroeconomic implications of this transition could be profound. With individuals directly exposed to the price of routine healthcare services, providers would face unprecedented pressure to rationalize pricing and improve service quality. Administrative simplification would be a natural consequence, as routine care transactions would no longer involve insurance billing, pre-authorization, or network negotiations. Healthcare GDP share could stabilize or even decline, reducing fiscal pressures on households and government budgets alike. Worker mobility would likely increase as the tether between employment and health benefits weakens, fostering labor market dynamism and entrepreneurial activity.

Nonetheless, the risks of systemic transition would be substantial. Vulnerable populations—those with low health literacy, chronic conditions, or unstable income—could be disproportionately affected if not adequately supported. Catastrophic-only insurance models would need carefully designed safety nets, such as income-adjusted subsidies for routine care expenses or automatic reinsurance mechanisms for high-frequency, medium-cost utilizers. Without such safeguards, there is a nontrivial risk of exacerbating health disparities, undermining the long-term fiscal and moral sustainability of the model.

Imagining a healthcare financing system that deploys insurance only for outlier expenses opens an extraordinary range of speculative futures. Testing these futures demands a concerted effort across private industry, state and federal regulators, and academic researchers. Self-insured employers, innovative insurers, state-based waivers, CMMI demonstration projects, and federally subsidized longitudinal research cohorts all represent crucial pathways for empirical validation. A new regulatory and actuarial infrastructure would be required to support this transformation, with a relentless focus on transparent data collection, rigorous outcomes measurement, and consumer protection. While the challenges are immense, so too is the promise: a healthcare system that is more affordable, efficient, and ultimately better aligned with the principles of true insurance and economic rationality.

Achieving credible validation of an outlier-only insurance model requires more than conceptual speculation; it demands rigorous empirical evaluation in statistically significant populations. Designing such evaluations presents a profound methodological and logistical challenge, one that intersects epidemiology, health economics, regulatory policy, and actuarial science. Several practical pathways exist, but success depends on careful population selection, experimental design, longitudinal follow-up, and the construction of datasets that permit precise attribution of cost and outcome variations to the intervention itself rather than to confounders.

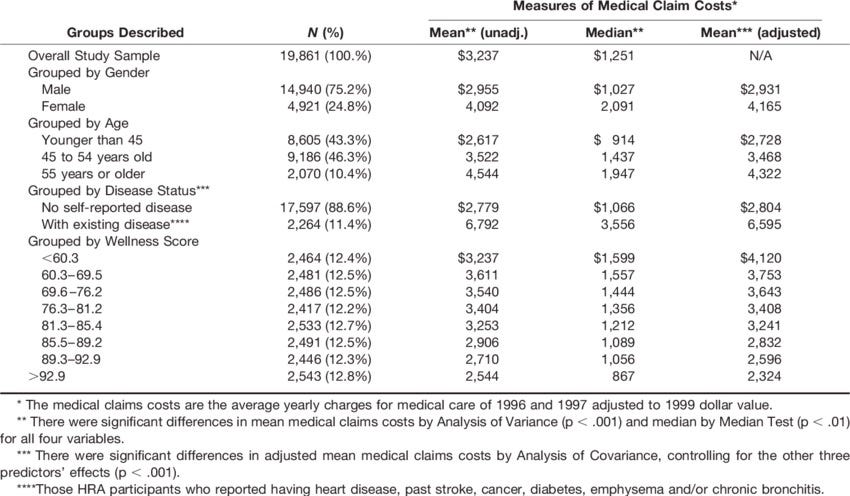

One of the most straightforward approaches is to leverage large self-insured employer groups to create natural experimental conditions. Firms with 10,000 or more covered lives offer an ideal substrate for statistically powered studies. Within these populations, randomized or quasi-randomized cohort assignment could be used to allocate some employees to catastrophic-only insurance products combined with fixed employer HSA contributions, while others remain on traditional comprehensive coverage. By stratifying cohorts based on baseline health risk scores (e.g., CMS-HCC, DxCG Intelligence, or proprietary predictive models), researchers can ensure comparable baseline characteristics, minimizing selection bias. A difference-in-differences analytic framework could then be applied to compare cost trajectories, utilization patterns, health outcomes, and patient satisfaction over a three-to-five-year horizon.

Such private sector experiments would require sophisticated data architecture. Administrative claims data alone would be insufficient. Integrating pharmacy claims, biometric data, self-reported health status surveys, and perhaps even real-time patient-generated data through wearable devices would enable multivariate analysis of both direct financial outcomes and indirect clinical endpoints. Critical endpoints would include not only total medical expenditure per member per year but also metrics like ambulatory care sensitive condition (ACSC) hospitalizations, medication adherence rates, preventive service uptake, and changes in functional health status. Statistical significance thresholds would need adjustment for multiple comparisons, with Bayesian adaptive trial methodologies offering potential advantages in dynamically allocating subjects based on emerging differences.

In parallel, state-based insurance markets present another opportunity for statistically significant real-world testing. Section 1332 waivers under the ACA empower states to modify insurance market rules, so long as coverage remains affordable, comprehensive, and deficit-neutral. States with relatively homogeneous populations and centralized insurance exchanges—such as Vermont, Hawaii, or Delaware—could submit waiver proposals to create new insurance tiers: catastrophic-only coverage combined with mandated HSA contributions or subsidized cash transfers. Enrollment would initially be voluntary but could be incentivized through premium rebates or tax credits.

Within these populations, robust comparative effectiveness research designs could be deployed. Propensity score matching could adjust for self-selection effects among individuals who opt into the catastrophic model versus traditional comprehensive plans. Time-to-event analyses, Cox proportional hazards models, and generalized estimating equations would enable estimation of differences in acute event rates, catastrophic claim incidence, and mortality across arms. States could partner with academic research consortia—such as PCORnet (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Network) or the NIH Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory—to ensure methodological rigor and transparent reporting of results.

Beyond voluntary pilots, Medicaid programs offer an even more structured laboratory for controlled experimentation. Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) serve populations that are often at the highest risk for both over-utilization and catastrophic events. CMMI could issue grants for states to pilot catastrophic-only Medicaid models for specific subpopulations: for example, working-age adults without complex chronic conditions. In such pilots, Medicaid could provide a fixed catastrophic insurance policy combined with a direct cash transfer calibrated to actuarial estimates of routine care needs, adjusted for local price indices.

Statistical power calculations would be paramount in designing these pilots. To detect, for example, a 10% reduction in total cost of care with 80% power and an alpha of 0.05 in a Medicaid population with a standard deviation of annual costs around $12,000, a sample size of approximately 6,400 participants per arm would be required. Stratification by social determinants of health indices—such as Area Deprivation Index or Social Vulnerability Index—would allow for subgroup analyses, identifying differential effects across socioeconomic strata. If pilots are cluster randomized at the MCO or county level, adjustments for intra-class correlation would be necessary to avoid overestimating effective sample sizes.

Regulatory support for data collection must underpin all these efforts. CMS could require participating insurers and Medicaid agencies to adopt standardized data submission formats, including encounter-level detail for all services rendered, time-stamped pharmaceutical dispensing data, and patient-reported outcomes using validated instruments such as PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) domains. Where possible, unique patient identifiers should be used to enable longitudinal linkage across administrative and clinical datasets while preserving privacy under HIPAA and 42 CFR Part 2 constraints.

In addition to quantitative outcomes, qualitative research must be integrated to fully understand the lived experience of participants under catastrophic-only insurance models. Structured interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic studies would illuminate barriers to care, behavioral adaptations, and perceptions of financial protection. These insights would be critical in refining benefit designs to maximize both economic efficiency and human dignity.

Recognizing that transitions to new insurance paradigms entail substantial behavior change, it would also be prudent to integrate behavioral economic experiments into pilot designs. For instance, studies could randomize participants to receive different levels of price transparency tools, decision support apps, or financial literacy interventions to assess their impact on care-seeking behavior and health outcomes under high-deductible, cash-driven models. Adaptive interventions, such as offering additional navigational support to individuals with poor early engagement metrics, could further optimize program effectiveness.

Finally, the broader economic impacts of catastrophic-only insurance models must be rigorously modeled using systems dynamics simulations and computable general equilibrium models. Microeconomic modeling could simulate individual household financial behavior, while macroeconomic models could estimate impacts on labor force participation, entrepreneurship rates, and aggregate healthcare spending. Longitudinal studies linking health insurance design to educational attainment, workforce productivity, and wealth accumulation would be critical to fully understand the societal ramifications of such a shift.

In summary, testing and validating a health insurance model focused solely on outlier expenses is an achievable but highly complex endeavor. It demands large, carefully selected populations; sophisticated experimental designs; comprehensive, high-fidelity data collection; and a willingness to embrace methodological pluralism, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches. Success would depend not only on actuarial precision and econometric rigor but on regulatory flexibility, stakeholder collaboration, and an unrelenting commitment to empirical evaluation over ideological assertion. If executed well, these pilots could illuminate a path toward a healthcare system that restores insurance to its original purpose—protection against the unpredictable—while empowering individuals to engage directly and thoughtfully with their everyday healthcare decisions.