The ACA’s Risk Transfer Program: The Reinsurance Safety Net That Frayed

Disclaimer: The thoughts here are my own and do not reflect those of my employer.

Table of Contents

1. Abstract

2. The Birth of a Safety Net

3. How the Mechanism Worked in Theory

4. When the Numbers Didn’t Add Up

5. The Legal Quicksand and Political Football

6. What Worked (Yes, Some Things Did)

7. What Broke and Why It Matters

8. Investor Lessons in Predictable Chaos

9. What Comes Next for Risk in Health Tech

10. Closing Thoughts

Abstract

1. The ACA risk transfer framework—composed of reinsurance, risk corridors, and risk adjustment—was designed to stabilize insurance markets during the rollout years.

2. While risk adjustment endures, reinsurance and risk corridors flopped due to political resistance, poor forecasting, and legal disputes.

3. Billions in unpaid obligations cratered CO-OPs and spooked private insurers, leading to reduced market competition.

4. The lessons for health tech investors lie in understanding how policy risk and capital structure interplay—especially when governments become silent partners.

5. Despite its stumbles, the program created key data and analytic infrastructure that now informs precision underwriting and risk modeling across digital health.

The Birth of a Safety Net

The Affordable Care Act’s risk transfer program was supposed to be the grown-up in the room—a quiet, technical framework that helped smooth the volatility of early marketplace insurance. Instead, it ended up as a case study in how good math can’t survive bad politics. If you’ve ever seen a startup try to model LTV/CAC without accounting for payer cycles, you’ve basically seen the same movie. The ACA’s architects built what looked like a well-designed shock absorber. It was the actuarial equivalent of anti-lock brakes for the individual insurance market. But a few years in, the whole thing started smoking on the highway.

When the ACA marketplaces went live in 2014, the concern was simple: insurers had no idea who was going to sign up. Would it be young, healthy people who barely used healthcare, or chronically ill patients who saw in the exchanges their first shot at affordable coverage? To keep insurers from running for the hills, the ACA set up a three-part stabilization system. Think of it as a risk management trinity: reinsurance (to backstop high-cost claims), risk corridors (to limit profit and loss volatility), and risk adjustment (to move money between insurers based on the relative sickness of their enrollees). On paper, these mechanisms were both elegant and boring. They were never meant to make headlines—just to quietly keep the risk pool solvent until the market matured.

How the Mechanism Worked in Theory

Reinsurance was the most straightforward. It reimbursed insurers for part of the cost of very high claims—essentially, if a patient’s care costs blew past a certain threshold, the federal government would cover a portion. The logic was sound: remove the tail risk of a few catastrophic cases destabilizing premiums. Risk corridors were a short-term financial buffer, promising to share gains and losses between insurers and the government for the first three years. Risk adjustment was the ongoing piece, a zero-sum transfer among insurers that persists today. The combination was meant to help insurers price confidently without overreacting to uncertainty.

When the Numbers Didn’t Add Up

But theory and practice rarely shake hands cleanly. The reinsurance program worked about as intended for its brief run. It lowered premiums by roughly 10 to 14 percent in its first two years, according to CMS data, and kept insurers solvent when claims volatility was highest. It was funded through broad assessments on all marketplace plans and ended up paying out around $25 billion between 2014 and 2016. By actuarial standards, that’s a win. But it was temporary by design. When the reinsurance program sunsetted in 2016, insurers lost a predictable source of stability, and premiums began to jump. States like Alaska later reintroduced their own state-level reinsurance programs to fill the void—proof that the idea worked even if the federal version didn’t stick.

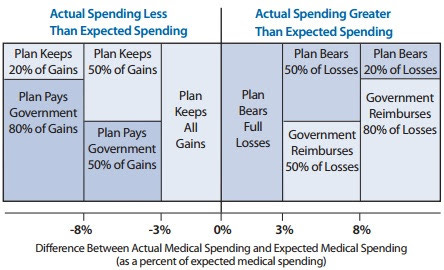

Risk corridors were where things went sideways. The intent was simple: if insurers’ medical costs ran much higher than expected, the government would cover a portion of the excess losses. If insurers made out like bandits, they’d pay part of the profits back. The mechanism was supposed to be budget-neutral over time. The problem was that Congress later decided it didn’t like the idea of insurers getting what looked like bailouts. In 2014, a Republican-controlled Congress added language to appropriations bills blocking the use of general funds to cover risk corridor shortfalls. Suddenly, the program could only pay out what it collected from profitable insurers. The math broke instantly.

The Legal Quicksand and Political Football

In the first year, insurers claimed about $2.9 billion in payments but only $362 million was available. That’s a payout ratio of roughly twelve cents on the dollar. Over three years, the unpaid total ballooned to more than $12 billion. Dozens of smaller insurers and CO-OPs—consumer-oriented nonprofit health plans meant to increase competition—collapsed under the weight of those unpaid receivables. For context, of the 23 original CO-OPs, only three survive today. This wasn’t just a budget snafu. It was a liquidity crisis dressed in policy language. Insurers had booked those receivables as assets; when they didn’t materialize, capital evaporated. The survivors either had deep reserves or got acquired. The rest went under.

The legal mess that followed was almost operatic. Dozens of insurers sued the federal government, arguing that risk corridor payments were binding obligations. The cases wound their way through the courts for years, with mixed early outcomes. Finally, in 2020, the Supreme Court weighed in—8 to 1 in Maine Community Health Options v. United States—ruling that the government indeed owed the payments. Congress’s later budget riders didn’t nullify the statutory commitment. The decision unlocked roughly $12 billion in long-delayed payments. Ironically, by the time the checks were cut, many of the original claimants no longer existed. Their estates or creditors collected the money. It was like winning the lottery posthumously.

What Worked (Yes, Some Things Did)

The risk adjustment program, the only surviving element, became the de facto core of ACA market stabilization. It’s conceptually elegant but politically fraught. Insurers with healthier-than-average members pay into the system, and those with sicker-than-average ones receive funds. In theory, this discourages cherry-picking and keeps competition focused on efficiency rather than avoiding risk. In practice, the model is only as good as its risk scoring methodology. Critics argue it rewards large incumbents with sophisticated coding operations and penalizes smaller players who can’t optimize risk capture at the same level. It’s like giving a handicap system to golfers but letting one group use laser rangefinders while the other gets a stick.

Despite all this turbulence, the risk transfer architecture did have measurable benefits. Premium volatility in the exchanges was lower than it might have been otherwise, and the system created a trove of data on utilization, morbidity, and cost patterns in the individual market. That data became raw fuel for today’s crop of health tech companies building predictive underwriting tools, alternative payment models, and population health analytics. The ACA’s messy execution indirectly seeded the infrastructure that now powers machine learning-based risk scoring and health data normalization startups.

What Broke and Why It Matters

Where it failed was in aligning political durability with financial precision. Health policy doesn’t happen in a vacuum; it happens in Congress, and Congress doesn’t do nuance well. The assumption that these programs would be allowed to operate apolitically for their intended duration was a category error. Once the risk corridor became a talking point about “bailing out insurance companies,” its fate was sealed. The irony is that those payments were meant to protect consumers, not insurers. Without them, premiums rose faster and plan choice shrank.

Investor Lessons in Predictable Chaos

From an investor’s lens, the ACA risk transfer episode is basically a case study in policy risk exposure. You can have an elegant model, pristine actuarial logic, and still end up insolvent because of appropriations politics. It’s like building a startup around a single CMS billing code and then watching that code get rescinded. Investors in health tech often underestimate how much of their portfolio risk is policy-correlated rather than market-correlated. The ACA’s experience shows that financial innovation in healthcare requires more than spreadsheets—it requires political resilience and redundancy.

There’s also a human capital lesson buried in this saga. The best-performing insurers post-ACA weren’t necessarily the biggest; they were the ones that could pivot fast when the government checks didn’t come. That agility—balancing regulatory literacy with operational elasticity—is the same muscle great health tech startups flex when reimbursement or compliance winds shift. Policy fluency has become a competitive moat.

What Comes Next for Risk in Health Tech

The ACA’s risk transfer experiment also reframed how the private sector thinks about shared-risk mechanisms. Today’s reinsurance and stop-loss models in value-based care contracts owe a lot to those early ACA frameworks. Private payers and digital-first risk-bearing entities are effectively building their own mini risk corridor systems—just without the government middleman. Venture-backed provider groups, especially those in Medicare Advantage and ACA markets, are creating internal actuarial teams that look suspiciously like scaled-down CMS departments. The lesson learned: if you want predictability, don’t rely on D.C. to provide it.

In a broader sense, the ACA’s risk transfer program underscores how fragile healthcare financing architecture can be when ideology outruns math. The program’s core principles—pooling risk, smoothing volatility, and encouraging competition—remain sound. The failure wasn’t in design but in execution. Like a startup that nails product-market fit but dies from a cash crunch, the program was undone by timing and liquidity, not lack of need.

Closing Thoughts

If you zoom out, there’s a weirdly hopeful takeaway. The marketplace didn’t collapse. It adapted. Insurers repriced, consumers adjusted, and the system stabilized—albeit at higher premiums and fewer choices. State-level reinsurance waivers now exist in more than a dozen states, often funded through pass-through savings from federal premium subsidies. These programs have reduced premiums by 15 to 20 percent on average. It’s a reminder that even when federal initiatives stumble, subnational innovation can pick up the slack.

For angel investors in health tech, the postmortem matters less than the playbook it leaves behind. The real lesson is that risk transfer is not just an insurance problem; it’s a data and capital allocation problem. As care models shift toward capitation and outcomes-based contracts, the ability to model, price, and hedge patient-level risk is gold. The ACA’s data infrastructure gave startups a baseline to build on, from digital reinsurers to data-driven TPAs to risk-bearing virtual care models. The next decade of healthcare investing will likely replay the same dynamics—where public policy creates a temporary inefficiency that private capital exploits before the government catches up again.

In short, the ACA’s risk transfer program tried to make a volatile market act rationally. It didn’t fully succeed, but it didn’t fail outright either. It gave the industry a crash course in systemic risk, data analytics, and the limits of actuarial optimism. For all its dysfunction, it accelerated the sophistication of payer analytics and forced investors to see health policy not as background noise but as the operating system itself. And if you’re investing in health tech, understanding that system’s quirks is the difference between a clean exit and a policy-induced write-off.

If you are interested in joining my generalist healthcare angel syndicate, reach out to treyrawles@gmail.com or send me a DM. We don’t take a carry and defer annual fees for six months so investors can decide if they see value before joining officially. Accredited investors only.