The Digital Transformation of Medical Knowledge: A Brief History of Health Information Interoperability (Extended Cyber Monday Offer)

For more daily long form essays on Healthcare Markets and Technology, similar to yesterday’s free article on FHIR and headless EHRs and the article below on the history of interoperability, I am extending 30% lifetime discounts on newsletter subscriptions through Cyber Monday.

Paid members get full access to seven longer form essays per week as well as the paid chat community where like minded health technology leaders have a place to share ideas and request topics for publication.

Offer link:

https://treyrawles.substack.com/25fea1eb

History of Healthcare Interoperability

For most of human history, medical knowledge was deeply personal. When our ancestors lived in small bands of hunter-gatherers, healing wisdom passed from one generation to the next through oral traditions and practical apprenticeships. A tribal healer would know every member of their small community intimately – their ailments, their family histories, their reactions to various remedies. This knowledge lived and died with each healer, rarely extending beyond the boundaries of their immediate group.

Fast forward to today, and a doctor in New York can instantly access the detailed medical history of a patient who normally lives in Tokyo but fell ill while visiting the United States. The doctor can see what medications the patient takes, their allergies, recent lab results, and previous surgeries – all translated automatically from Japanese to English. This remarkable capability represents one of the greatest yet least celebrated transformations in human history: the shift from isolated pockets of medical knowledge to interconnected systems of health information that span the globe.

But how did we get here? How did we transform from a world where medical information existed primarily in the minds and private notebooks of individual healers to one where health data flows seamlessly across institutions, cities, and continents? This is the story of health information interoperability – a tale not just of technology, but of human ambition, cooperation, and our species' relentless drive to better understand and care for ourselves.

The Age of Paper

For most of recorded history, medical records were simple affairs. Ancient Egyptian papyri from around 1600 BCE show us that physicians kept basic notes about their patients' conditions and treatments. These records were more like personal journals than formal medical documents, helping healers remember what worked and what didn't for different ailments.

The tradition of keeping medical records continued through the ages, but remained largely personal and idiosyncratic until well into the modern era. Even as late as the 19th century, most doctors maintained their patient information in pocket notebooks or simple ledgers. These records rarely left the physician's possession and died with them – their knowledge forever lost to time.

The first real revolution in medical record-keeping came with the rise of modern hospitals in the late 1800s. As healthcare became more institutionalized, the need for standardized documentation became apparent. Hospitals began creating dedicated medical records departments, and the concept of the patient chart was born. For the first time, multiple healthcare providers could access and contribute to the same record, marking humanity's first tentative steps toward true health information sharing.

The Paper Prison

By the mid-20th century, larger hospitals were drowning in paper. Medical knowledge was expanding exponentially, diagnostic tests were multiplying, and documentation requirements were growing ever more complex. A single patient's file could contain hundreds of pages spread across multiple volumes. Finding specific information often meant hunting through rooms full of filing cabinets, and sharing records between facilities required physically copying and mailing documents – a process that could take weeks.

This "paper prison" created numerous problems. Critical medical information was frequently unavailable when needed, leading to delayed or inappropriate care. Patients who saw multiple providers had their medical histories fragmented across different locations. Valuable clinical data that could have advanced medical research remained locked away in filing cabinets, inaccessible to scientists and researchers.

The situation was ripe for disruption, and the arrival of computers in the 1960s seemed to offer a solution. Early pioneers in medical informatics began dreaming of electronic health records that could be easily stored, retrieved, and shared. But they would soon discover that digitizing health information was only the first step in a much longer journey.

The Digital Dawn

The first electronic health records systems emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, developed by forward-thinking academic medical centers. These early systems were primarily focused on clinical laboratory reporting and administrative tasks rather than comprehensive patient care documentation. The technology was primitive by today's standards – most used text-based interfaces and could only handle basic data types.

One of the earliest and most influential systems was the Problem-Oriented Medical Information System (PROMIS) developed at the University of Vermont. PROMIS introduced the revolutionary concept that medical records should be organized around patient problems rather than provider encounters. This seemingly simple idea would profoundly influence the future development of electronic health records.

But these early systems were islands unto themselves. Each was custom-built for its institution, using unique data formats and structures. They couldn't talk to each other any more than paper records could. The dream of truly shareable electronic health information remained elusive.

The Standards Revolution

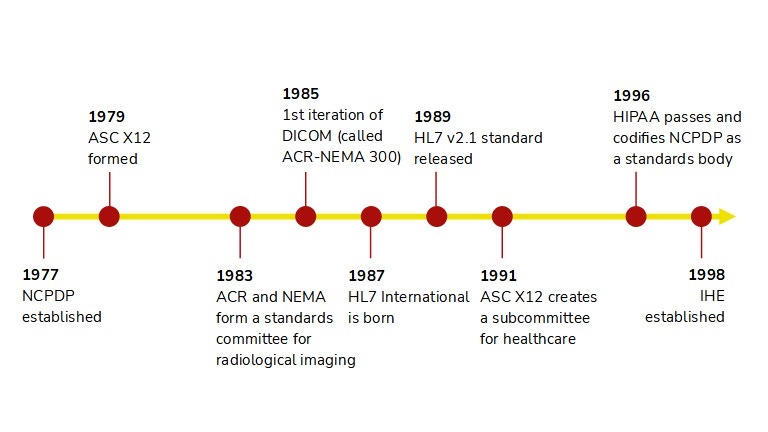

As healthcare organizations began adopting various electronic systems in the 1980s, it became clear that some form of standardization would be necessary for these systems to communicate. This realization sparked what we might call the "standards revolution" – a massive collective effort to create common languages and protocols for health information exchange.

The first major breakthrough came with the development of HL7 (Health Level Seven) in 1987. Named for the seventh layer of the ISO communications model, HL7 provided a standard format for exchanging clinical and administrative data between different healthcare applications. For the first time, there was a common language that different health information systems could use to communicate.

But HL7 was just the beginning. The 1990s and early 2000s saw the emergence of numerous other healthcare data standards: DICOM for medical imaging, LOINC for laboratory observations, SNOMED CT for clinical terminology, and many others. Each addressed a different aspect of the health information ecosystem, gradually building the foundation for true interoperability.

The Internet Changes Everything

The rise of the Internet in the 1990s transformed the possibilities for health information exchange. Suddenly, there was a universal network that could connect any two points on the globe. The technical barriers to sharing health information across vast distances began to fall away.

This new connectivity sparked ambitious dreams. Healthcare visionaries imagined a world where any provider could instantly access any patient's complete medical history from anywhere. Patients would control their own health data, sharing it seamlessly with providers of their choice. Population health researchers would analyze vast pools of clinical data to uncover new insights about disease and treatment.

But these dreams crashed against hard realities. Technical standards alone weren't enough to achieve true interoperability. There were thorny questions of patient privacy, data security, and consent to be resolved. Different countries had different laws and regulations about health information sharing. And perhaps most significantly, many healthcare organizations saw their patient data as a valuable asset they were reluctant to share.

The Age of Meaningful Use

The first decade of the 21st century saw growing recognition that market forces alone wouldn't achieve the level of health information interoperability needed to improve healthcare quality and efficiency. Government intervention would be necessary to break down the barriers to data sharing.

In the United States, this led to the HITECH Act of 2009 and the subsequent "Meaningful Use" program, which provided financial incentives for healthcare providers to adopt certified electronic health record systems and use them in ways that supported information sharing. Similar initiatives emerged in other countries, though with varying approaches and degrees of success.

These programs dramatically accelerated the adoption of electronic health records. By 2015, over 80% of U.S. hospitals had adopted at least a basic EHR system, up from just 9% in 2008. But quantity didn't necessarily equal quality. Many of these systems still struggled to share information effectively, leading to growing frustration among both providers and patients.

The API Revolution

As healthcare grappled with interoperability challenges, the broader technology world was experiencing a revolution in how computer systems share information. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) had emerged as the standard way for different software systems to communicate, powering everything from social media platforms to e-commerce sites.

Healthcare began to take notice. In 2014, a group of healthcare organizations and technology companies came together to create FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) – a new standard that brought modern web technologies to healthcare data exchange. FHIR combined the best of previous healthcare standards with contemporary API approaches, making it easier for developers to create interoperable healthcare applications.

The impact was transformative. FHIR's relative simplicity and flexibility attracted developers who had previously avoided healthcare due to its complexity. Major technology companies like Apple, Google, and Microsoft began incorporating FHIR into their health initiatives. A new ecosystem of healthcare apps and services began to emerge.

The Age of Patient Empowerment

As we move through the 2020s, we're entering what might be called the Age of Patient Empowerment in health information interoperability. New regulations in many countries now require healthcare providers to give patients electronic access to their health information and the ability to share it with applications of their choice.

This shift represents a fundamental change in how we think about health information. Rather than viewing medical records as institutional assets to be controlled by healthcare providers, we're moving toward a model where health information is seen as belonging to the patient, with providers serving as stewards rather than owners of this data.

The implications are profound. Patients can now aggregate their health information from multiple providers, share it with family members or caregivers, and use it with various health and wellness apps. They can contribute their own data from wearable devices and home monitoring equipment. They can participate in research by sharing their data with scientists studying their conditions.

The Challenges Ahead

Despite enormous progress, significant challenges remain in achieving true health information interoperability. Technical standards continue to evolve, requiring constant updates to systems and procedures. Privacy and security concerns grow more complex as health information becomes more mobile. Questions of data quality and reliability become more pressing as information flows more freely between systems.

Moreover, new technologies like artificial intelligence and genomic medicine are generating new types of health data that existing interoperability standards weren't designed to handle. The volume of health data is exploding, creating challenges for storage, transmission, and analysis.

Perhaps most fundamentally, we're still grappling with questions about the proper balance between data sharing and privacy, between standardization and innovation, between individual control and collective benefit.

The Future of Health Information

Looking ahead, we can see the outlines of where health information interoperability might be heading. Artificial intelligence will increasingly help us make sense of the vast amounts of health data we're collecting. Blockchain and similar technologies might provide new ways to ensure the security and integrity of health information as it moves between systems.

The distinction between clinical and consumer health data will likely continue to blur. Our health records might eventually include not just traditional medical information but also data from our smartphones, smart watches, smart homes, and even smart cities. This expanded view of health information could give us unprecedented insights into the factors that influence our health and well-being.

We might see the emergence of "health information commons" – shared pools of anonymized health data that can be used for research and public health purposes while protecting individual privacy. These could accelerate medical research and help us better understand and respond to health challenges at a population level.

The Human Element

As we marvel at these technological achievements and possibilities, it's worth remembering that at its core, health information interoperability is about human beings caring for other human beings. The tribal healer who knew every member of their community intimately had something we risk losing in our age of digital health records – a deep personal connection with those they cared for.

The challenge for the future will be to use our increasingly sophisticated health information systems not to replace these human connections, but to enhance them. To free healthcare providers from bureaucratic busywork so they can spend more time with patients. To give patients better understanding and control of their health. To help us all make better decisions about our health and healthcare.

Conclusion

The journey from isolated pockets of medical knowledge to interconnected global health information systems represents one of humanity's great achievements. It's a story of technological innovation, certainly, but also of human cooperation and shared purpose on an unprecedented scale.

As we face new health challenges – from emerging diseases to aging populations to climate change impacts on health – our ability to share and make use of health information will become ever more critical. The continuing evolution of health information interoperability will play a vital role in helping us meet these challenges.

Just as the invention of writing allowed human knowledge to transcend individual memory, and the printing press allowed it to transcend physical distance, digital health information interoperability is allowing medical knowledge to transcend institutional and national boundaries. It's helping us move toward a future where the right information is available to the right person at the right time to make the best possible decisions about health and healthcare.

This transformation isn't complete, and the challenges ahead are significant. But the direction is clear: we're moving from a world of isolated medical knowledge to one of connected health information, from institutional control to patient empowerment, from reactive to proactive healthcare. It's a journey that began with the first healer who decided to write down their observations, and it continues today with every new advance in health information technology.

The story of health information interoperability is, in the end, a very human story. It's about our eternal quest to better understand ourselves and our health, our drive to share knowledge for the common good, and our hope that by working together, we can build a healthier future for all humanity.