The Prescription Drug Pricing Puzzle: PBMs, Specialty Drugs, and the Cost Plus Disruption

Introduction

The American healthcare system stands as a paradox of innovation and inefficiency, particularly within its pharmaceutical sector. While breakthrough medications continue to emerge from research laboratories, the path these drugs take to reach patients is fraught with complexity, opacity, and often inexplicable costs. The LinkedIn post shared by Erin L. Albert—a professional with the rare combination of pharmacy, legal, and business expertise—offers a window into this complicated world, highlighting a troubling pattern of price markups on generic medications classified as "specialty drugs."

As I examine the heatmap from the Federal Trade Commission's interim report and Albert's commentary, a story emerges about how the pharmaceutical supply chain operates today, how language and classification can be weaponized to justify higher prices, and how new market entrants like Mark Cuban's Cost Plus Drug Company are attempting to bypass this intricate system to deliver medications at more transparent and affordable prices. This essay will delve into these intersecting narratives, exploring the current market dynamics, the questionable concept of "specialty drugs," and the potential for disruption in a system that has proven resistant to change.

The Pharmaceutical Market: A Complex Web of Interests

The Evolution of the Modern Drug Supply Chain

To understand the significance of Albert's observations, we must first comprehend how prescription medications move from manufacturers to patients in today's market. Unlike the relatively straightforward transaction of purchasing most consumer goods, prescription drugs follow a convoluted path through a landscape populated by powerful intermediaries.

Imagine you've been prescribed a medication for a chronic condition. The journey of that pill to your medicine cabinet began long before your doctor wrote the prescription. A pharmaceutical company invested years and potentially billions of dollars in research, development, clinical trials, and regulatory approval processes. Once approved, the drug enters a distribution system that appears designed to obscure rather than clarify its true cost.

The traditional pharmaceutical supply chain involves manufacturers who create the drugs, wholesalers who purchase and distribute them in bulk, and pharmacies that ultimately dispense them to patients. Health insurers provide coverage for these medications, determining what portion patients will pay out-of-pocket. This system evolved with relatively clear boundaries between these entities, each fulfilling a distinct role.

However, over the past three decades, these boundaries have blurred considerably. Companies at different levels of the supply chain have merged, acquired one another, or formed strategic alliances, creating massive healthcare conglomerates with fingers in multiple pies. This vertical integration, as economists call it, has fundamentally altered the incentives and power dynamics within the pharmaceutical market.

The Rise of Pharmacy Benefit Managers

At the center of this transformation are Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs. These entities emerged in the 1960s as simple administrators processing prescription drug claims between pharmacies and insurers. Today, they have evolved into powerful market forces that influence nearly every aspect of prescription drug access and pricing.

Modern PBMs wear many hats. They negotiate with drug manufacturers for rebates and discounts, create formularies that determine which medications receive preferred coverage, establish networks of pharmacies where patients can fill prescriptions, process claims, and even operate their own mail-order and specialty pharmacies. They serve as gatekeepers between patients and medications, wielding enormous influence over which drugs people can access and at what cost.

The PBM market has consolidated dramatically, with three dominant players now controlling approximately 80% of prescription claims in the United States: CVS Caremark (owned by CVS Health, which also owns Aetna insurance and CVS Pharmacy), Express Scripts (owned by Cigna, a major health insurer), and OptumRx (owned by UnitedHealth Group, parent company of the nation's largest health insurer). This consolidation, coupled with vertical integration, has raised concerns about market power, conflicts of interest, and the impact on drug pricing and patient access.

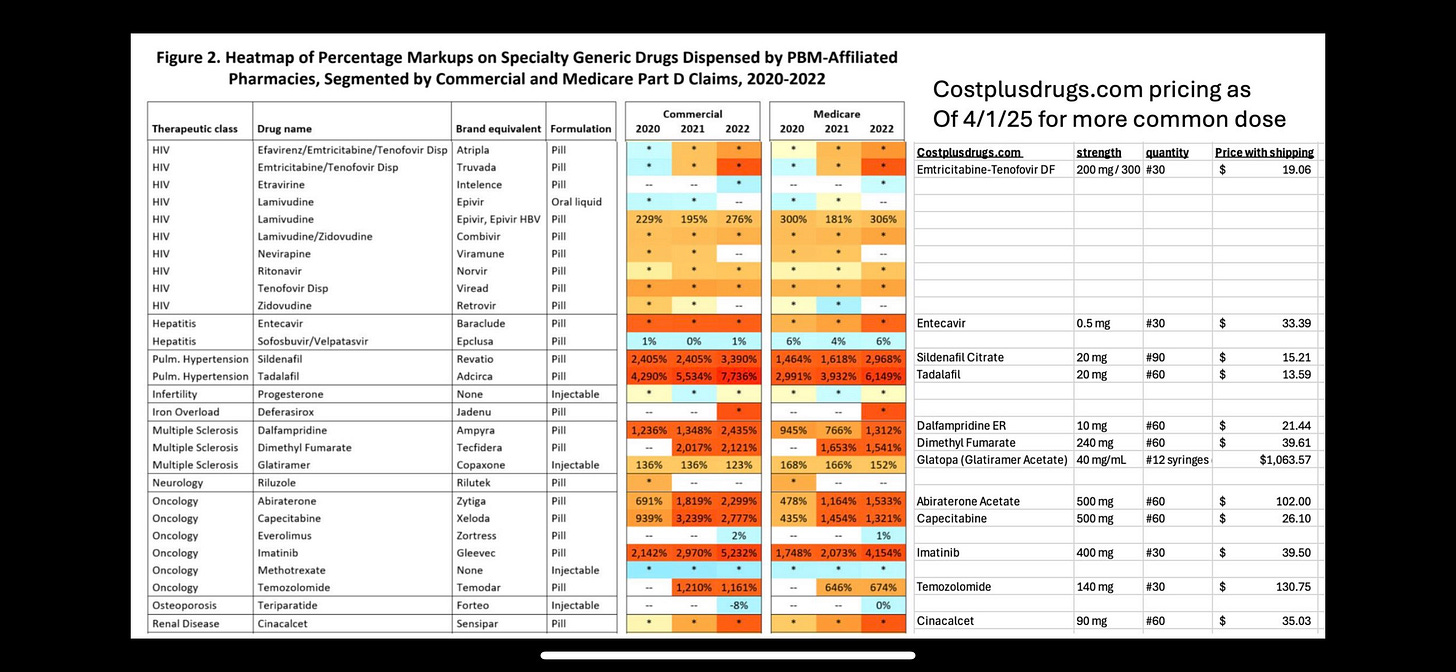

The heatmap in the FTC report referenced by Albert provides a striking visualization of how this market concentration might be affecting drug prices. The document displays percentage markups on generic medications classified as "specialty drugs" when dispensed by PBM-affiliated pharmacies, with some showing markups of several thousand percent. These eye-popping figures raise fundamental questions about how the pharmaceutical market functions and whom it ultimately serves.

The "Specialty Drug" Designation: A Marketing Creation?

Deconstructing a Lucrative Label

"There are no specialty drugs," Albert boldly declares in her LinkedIn post. "There are only prescription drugs, OTCs, and supplements." This statement cuts to the heart of a contentious issue in pharmaceutical pricing—the very definition and purpose of classifying certain medications as "specialty drugs."

Traditionally, the term "specialty drug" referred to medications with specific characteristics that justified special handling or distribution channels. These might include biologics requiring refrigeration, medications administered through complex methods like infusion, drugs treating rare conditions and requiring specialized patient support, or particularly high-cost treatments. This classification made sense when it described medications that genuinely required different handling or expertise than traditional oral medications dispensed at community pharmacies.

However, as Albert suggests, the definition of "specialty drugs" has expanded over time, potentially becoming a strategic tool rather than a purely descriptive category. The boundaries of what constitutes a "specialty medication" have become increasingly blurry, with PBMs and insurers sometimes applying the designation to medications that don't necessarily fit the original criteria. This expansion has coincided with the growth of PBM-owned specialty pharmacies, creating a situation where entities can benefit from directing prescriptions to their affiliated pharmacies and applying substantial markups.

The FTC report's heatmap illustrates this concern vividly. Many of the drugs showing the highest percentage markups are generic versions of brand-name medications. Once a brand-name drug loses patent protection, generic competition typically drives prices down dramatically. Generic medications are bioequivalent to their brand-name counterparts and undergo the same FDA approval process for safety and efficacy, but they generally cost 80-85% less due to lower research and development investments.

Yet the heatmap shows these generic medications being marked up by thousands of percentage points when dispensed through PBM-affiliated pharmacies. For example, generic imatinib (used to treat certain cancers) shows markups exceeding 5,000% in commercial plans and 4,000% in Medicare Part D plans in 2022. Similar patterns appear for medications treating pulmonary hypertension, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions.

The Financial Impact of Classification

These markups have real-world consequences for patients, employers, and government programs funding healthcare. When a medication is classified as a "specialty drug," it often triggers different coverage rules, including:

Higher patient cost-sharing, sometimes with coinsurance (a percentage of the total cost) rather than fixed copayments

Requirements to use specific specialty pharmacies, often owned by the PBM

Additional prior authorization requirements

Quantity limits or other utilization management tools

Different methods of calculating pharmacy reimbursement

For patients, these differences can mean substantially higher out-of-pocket costs and additional hurdles to accessing needed medications. For employers and government programs, they translate to higher overall healthcare spending.

Albert's juxtaposition of the FTC heatmap with pricing from Cost Plus Drugs tells a compelling story. The same medications showing thousands of percentage points in markup through traditional channels are available at dramatically lower prices through Mark Cuban's venture. This stark contrast raises fundamental questions about the necessity and justification for these markups, and whether the "specialty" designation serves patient care or financial interests.

Mark Cuban's Cost Plus Drugs: A Disruptive Force

A New Model Emerges

Against the backdrop of complex pricing schemes and multilayered distribution channels, Mark Cuban's Cost Plus Drug Company represents a radical simplification. Launched in 2022, this online pharmacy operates on a transparent pricing model: the actual cost of the drug plus a 15% markup, a $3 pharmacy dispensing fee, and $5 for shipping.

This straightforward approach stands in stark contrast to the byzantine pricing mechanisms that characterize the traditional pharmaceutical supply chain. There are no hidden fees, no mysterious rebates, no classification schemes that trigger different pricing tiers—just the actual cost plus a transparent markup.

The pricing comparison Albert presents in her post highlights the potential impact of this model. Medications showing markups of thousands of percentage points in PBM-affiliated pharmacies are available through Cost Plus Drugs at prices that reflect their true manufacturing costs plus modest, transparent markups. For example, while the FTC report shows massive markups on medications like sildenafil and tadalafil (used for pulmonary hypertension), Cost Plus Drugs offers these medications for $15.21 and $13.59 respectively for a month's supply.

This dramatic price difference illuminates the inefficiencies—or perhaps more accurately, the profit extraction—occurring within the traditional pharmaceutical supply chain. By circumventing PBMs and their complex network of rebates, formularies, and tiered pricing, Cost Plus Drugs demonstrates that many medications can be provided at a fraction of their current cost while still maintaining a sustainable business model.

Bypassing the Middlemen

Cuban's venture accomplishes this feat by eliminating or minimizing the role of middlemen in the pharmaceutical supply chain. Instead of relying on wholesalers, PBMs, and traditional retail pharmacies, Cost Plus Drugs purchases medications directly from manufacturers or authorized distributors and dispenses them directly to patients.

This direct-to-consumer model removes layers of markup and profit extraction that characterize the traditional system. While Cost Plus Drugs initially focused on generic medications not covered by insurance (requiring patients to pay out-of-pocket), it has begun working with some employers and third-party administrators to process insurance claims, potentially extending its impact to insured patients as well.

The company has also taken steps to further control costs by building its own pharmaceutical manufacturing facility in Dallas, Texas. This vertical integration—but in the direction of controlling manufacturing rather than insurance and pharmacy benefits—aims to further reduce costs and ensure supply chain reliability for commonly prescribed generic medications.

Cuban's approach represents a form of market-based disruption rather than a comprehensive policy solution. By creating a transparent alternative to the existing system, Cost Plus Drugs puts pressure on traditional players to justify their pricing practices and potentially forces incremental changes in how medications are priced and distributed.

The Structural Challenges of Pharmaceutical Pricing

Beyond Individual Actors: System-Level Issues

While Albert's post and the FTC report highlight concerning practices by PBMs and their affiliated pharmacies, it's important to recognize that these issues reflect structural problems within the American healthcare system rather than simply the actions of malevolent actors. The pharmaceutical pricing ecosystem has evolved over decades into its current form through a series of policy decisions, market forces, and incremental changes.

The American approach to pharmaceutical coverage differs significantly from those of other developed nations. While countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia have government agencies that negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers and make centralized coverage decisions, the United States has historically relied on a fragmented system of private negotiations. This fragmentation creates complexity that can be exploited through strategic classification, differential pricing, and opacity.

The concept of "specialty drugs" emerged within this context as a way to carve out certain medications for different handling and pricing. As Albert suggests, what began as a potentially legitimate distinction based on handling requirements or administration methods has expanded into a broader classification that may serve financial interests as much as patient care needs.

The vertical integration of PBMs with insurers and pharmacies further complicates this picture. When a single corporate entity owns the insurance plan, the PBM, and the specialty pharmacy, internal transfers between these divisions can obscure the true economics of prescription drug distribution. Money might move from one division to another within the same parent company, making it difficult for outsiders—including regulators, employers purchasing benefits, and patients—to understand the true costs and markups involved.

The Data Transparency Problem

One of the most significant challenges in addressing pharmaceutical pricing issues is the lack of transparency around actual costs and prices. The posted prices of medications bear little relationship to what various parties actually pay. Manufacturers set list prices but offer rebates and discounts to PBMs and insurers. PBMs negotiate different rates with different pharmacies. Patients with different insurance plans pay different amounts for the same medication at the same pharmacy.

This opacity makes it extremely difficult to identify excessive markups or inappropriate classification decisions without access to proprietary data. The FTC report referenced by Albert represents a rare window into these practices, made possible by the agency's investigative authority. For everyday market participants—patients, employers, healthcare providers—this information remains largely hidden.

Cost Plus Drugs' transparent pricing model contrasts sharply with this opacity. By clearly stating the actual cost of each medication and applying a consistent, transparent markup, Cuban's venture provides a reference point against which traditional pricing can be compared. This transparency itself represents a form of disruption in a market characterized by information asymmetry.

Potential Paths Forward

Market-Based Solutions and Policy Interventions

Albert concludes her post with a provocative suggestion: "If we really want to make an impact on the cost of prescription drugs, we need to simply stop working with the big 3 PBMs that control 80%+ of prescription reimbursements in the USA, and who also happen to own their own vertically integrated pharmacies." This statement acknowledges both the market concentration that characterizes the PBM industry and the potential conflicts of interest created by vertical integration.

While abandoning the dominant PBMs entirely might not be feasible for many employers and health plans in the short term, there are both market-based and policy approaches that could address the issues highlighted in Albert's post:

Increased transparency requirements: Regulations requiring PBMs to disclose rebates, actual acquisition costs, and markup percentages could help address information asymmetry in the market. Several states have enacted laws requiring various forms of PBM transparency, though their effectiveness varies.

Alternative PBM models: Some newer PBMs operate on "pass-through" models that charge administrative fees rather than retaining portions of rebates or spreads between what they pay pharmacies and what they charge plan sponsors. These models align incentives differently and may reduce conflicts of interest.

Direct contracting: Some employers have begun contracting directly with pharmacies or establishing their own pharmacy networks, bypassing traditional PBM arrangements entirely for some or all of their prescription benefits.

Regulatory oversight: Enhanced scrutiny from agencies like the FTC, as evidenced by the interim report referenced by Albert, could help identify and address potentially anticompetitive practices.

Comprehensive reform: More sweeping policy changes, such as allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers (partially implemented through the Inflation Reduction Act) or establishing an independent drug pricing review board, could fundamentally alter market dynamics.

The Promise and Limitations of Cuban's Approach

Mark Cuban's Cost Plus Drug Company represents an important experiment in pharmaceutical distribution, demonstrating that medications can be provided at significantly lower costs through a simplified, transparent supply chain. However, its model also has limitations that may constrain its impact on the broader market:

Insurance integration challenges: While Cost Plus Drugs has begun working with some employers and administrators, integrating with the dominant insurance system remains a challenge. Many patients prefer to use their insurance coverage rather than paying out-of-pocket, even if the out-of-pocket price might be lower.

Limited formulary: Cost Plus Drugs initially focused on generic medications, which represent the majority of prescriptions by volume but a minority of spending. Brand-name medications still under patent protection, which drive much of pharmaceutical spending, remain subject to the traditional pricing system.

Specialty medication handling: Some medications truly do require special handling, administration support, or patient monitoring. The Cost Plus model may need to evolve to address these legitimate needs without recreating the problematic aspects of the current specialty pharmacy system.

Scale and reach: Building a nationwide pharmacy operation capable of challenging entrenched players requires significant capital investment and time. While Cuban has the resources to support this venture, scaling it to serve a substantial portion of the market presents logistical and operational challenges.

Despite these limitations, the Cost Plus model provides important proof that alternative approaches to pharmaceutical distribution are possible. By demonstrating that many medications can be provided at a fraction of their current prices while maintaining quality and service, Cuban's venture puts pressure on traditional players to justify their practices and potentially drives incremental changes throughout the system.

Conclusion: Toward a More Rational Pharmaceutical Market

The issues highlighted in Erin Albert's LinkedIn post and the FTC report she references reflect deep structural problems within the American pharmaceutical distribution system. The classification of certain generic medications as "specialty drugs" and the application of massive markups when dispensed through PBM-affiliated pharmacies raise serious questions about whether the current system serves the interests of patients, employers, and public programs funding healthcare.

Mark Cuban's Cost Plus Drug Company offers one potential path forward, demonstrating that transparency, simplified distribution, and reasonable markups can dramatically reduce the cost of many medications. However, comprehensive solutions will likely require a combination of market-based innovation, regulatory oversight, and potentially broader policy reform to address the full scope of pharmaceutical pricing challenges.

As patients, healthcare providers, employers, and policymakers grapple with these issues, the stark contrast between traditional pricing practices and transparent alternatives like Cost Plus Drugs provides valuable evidence that the status quo is not inevitable. The extraordinary markups documented in the FTC report are not necessary components of a functioning pharmaceutical market but rather symptoms of a system that has evolved to extract value at multiple levels of the supply chain.

The path toward a more rational pharmaceutical market will not be simple or straightforward. It will require untangling complex contractual relationships, addressing entrenched financial interests, and rethinking how we classify, distribute, and pay for medications. However, the potential benefits—more affordable medications, reduced financial burden on patients, and more sustainable healthcare spending—make this difficult work essential.

Albert's provocative conclusion—"There are no specialty drugs"—cuts to the heart of the matter. While some medications may indeed require special handling or administration, the expansion of the "specialty" designation appears to have far outpaced legitimate clinical needs. Recognizing that many of these classifications serve financial rather than clinical purposes represents an important first step toward creating a more transparent, affordable, and patient-centered pharmaceutical market.