The standardization trap: why deploying AI agents in healthcare require requires a Palantir-style approach to “forward deployed” custom workflow engineering

Abstract

This essay examines the tension between standardized AI agent infrastructure and the custom workflow engineering required to actually make AI agents useful in clinical and administrative healthcare settings. The core argument is that roughly 60-70% of a healthcare AI agent tech stack can be standardized (LLM APIs, vector databases, orchestration layers, auth/compliance scaffolding), but the remaining 30-40% demands something closer to Palantir’s forward deployed engineering (FDE) model, where engineers and domain experts are embedded on-site to understand, map, and programmatically encode workflows that are often undocumented, inconsistent, and deeply human. Key topics covered include the anatomy of a healthcare AI agent stack, what makes healthcare workflows uniquely resistant to generic automation, the economics and tradeoffs of the FDE model, and what this means for startups, health systems, and investors deploying or funding agent-based solutions.

Key data points referenced include:

- 2024 Rock Health report noting 70% of health AI pilots fail to scale beyond proof of concept

- McKinsey estimate that healthcare administrative costs exceed $350B annually in the US

- Palantir’s FDE model origins at DoD/CIA deployments and translation to commercial healthcare

- LangChain, LlamaIndex, CrewAI as examples of standardized orchestration layers

- FHIR R4 adoption rates and interoperability gap data from ONC

- Time-to-value benchmarks from enterprise AI deployments across health systems

Table of Contents

The agent hype problem

What actually lives in a healthcare AI agent stack

The standardizable 60-70%: what you can commoditize

The custom 30-40%: where health systems actually differ

The Palantir FDE model and why it translates

Economics of the FDE approach for startups and health systems

What this means for investors

Where this is all going

The agent hype problem

Everyone in health tech right now is either deploying AI agents, claiming to deploy them, or on a panel about why they’re going to deploy them soon. The vendor landscape has gotten comically overcrowded. There are “AI agents for prior auth,” “AI agents for clinical documentation,” “AI agents for revenue cycle,” and several dozen companies all pitching the same slide showing a robot completing tasks a human used to do. Most of it is noise. Some of it is genuinely interesting. The challenge for operators and investors is figuring out which is which, and the best way to do that is to get very precise about what these systems actually require to work.

The thing that distinguishes healthcare from most other verticals deploying agent tech is that the workflows are a mess, the data is a mess, the regulatory environment is punishing, and the end users are either clinicians who will not tolerate friction or administrative staff who have been burned by technology promises before. You can’t just drop a general-purpose agent into a hospital billing department and expect it to work. The agent needs to understand that this particular health system uses a 15-year-old Epic instance with a custom charge description master, that their coders follow a hybrid ICD-10/internal taxonomy, and that there’s one person in the Medicaid team who manually overrides the system every Tuesday because of a payer contract quirk nobody has fully documented.

This is the core tension in healthcare AI agent deployment: the infrastructure layer is becoming commoditized fast, but the workflow layer remains stubbornly bespoke. Getting that balance right is the difference between a pilot that works and a product that scales.

What actually lives in a healthcare AI agent stack

Before getting into what can and can’t be standardized, it helps to be explicit about what a full-stack healthcare AI agent actually consists of. Most people collapse this into “the model plus some integrations” which is too simple and leads to bad architectural decisions.

A reasonably complete healthcare AI agent stack has about six layers. At the foundation you have the LLM or model layer, which is the reasoning engine. Above that sits the memory and retrieval layer, which handles how the agent accesses relevant context, whether from a vector database, structured SQL, or document stores. The orchestration layer sits on top of that and manages multi-step task execution, tool use, and agent-to-agent coordination. Then there’s the integration layer, which handles connections to EHRs, payer portals, lab systems, and other health IT endpoints. Above that is the workflow and rules layer, which encodes the actual decision logic and process flows specific to the use case and organization. And at the top is the interface and trust layer, which includes the user-facing surface, audit logging, explainability outputs, and human-in-the-loop mechanisms that regulators and risk-averse health system CTOs care deeply about.

The interesting question is not “what are these layers” but “which of them can you buy off the shelf versus what do you have to build yourself.” The answer varies significantly by layer, and understanding where the customization burden falls is essential for anyone making a build/buy/partner decision.

The standardizable 60-70%: what you can commoditize

Let’s start with the good news, which is that a substantial portion of a healthcare AI agent stack is now genuinely commoditized or close to it. Foundational model access is a solved problem. Whether it’s GPT-4o, Claude Sonnet, Gemini 1.5 Pro, or one of the open-weight alternatives like Llama 3.1 or Mistral, the raw reasoning capability you need to power most administrative and certain clinical agent tasks is accessible via API with pricing that has dropped precipitously in the last 18 months. Token costs for input have fallen something like 90% since GPT-4 launched in 2023. That’s not a rounding error, that’s a structural shift in the economics of building on top of foundation models.

The orchestration layer is also largely commoditized at this point. LangChain, LlamaIndex, LangGraph, CrewAI, AutoGen from Microsoft, and a handful of others provide solid frameworks for building multi-step, tool-using agents. None of them are perfect. LangChain in particular has a reputation for over-engineering simple use cases. But the core capability, managing an agent loop that can call tools, route between sub-agents, maintain state across steps, and handle errors, is well-covered by open-source or low-cost commercial tooling. You don’t need to build an orchestration layer from scratch in 2024 unless you have a very specific reason.

Vector databases and retrieval infrastructure are similarly commoditized. Pinecone, Weaviate, Qdrant, pgvector inside Postgres, Chroma for lightweight applications. The market has standardized reasonably well here and the cost per query is trivial at most healthcare administrative use case scales. Healthcare does add complexity in terms of data volumes (large imaging datasets being the obvious exception) but for text-heavy workflows like clinical documentation, prior auth, and coding, standard retrieval infrastructure works fine.

Authentication, RBAC, and audit logging infrastructure is increasingly well-served by vendors who have built specifically for regulated industries. The SOC 2, HIPAA BAA, and increasingly FedRAMP compliance layers are not easy to build but they are well-understood, and there are platforms that abstract most of this away. Similarly, basic integration tooling for health data, FHIR APIs, HL7 v2 parsing, CCD/CCDA document handling, has matured substantially. The ONC’s interoperability rules under the 21st Century Cures Act pushed health systems and EHR vendors to build FHIR R4 APIs, and while adoption is uneven (somewhere around 60-70% of large health systems have functional FHIR endpoints as of late 2024 per ONC tracking data), you have real programmatic access to clinical data at a scale that wasn’t possible three years ago.

So the standardizable portion of the stack covers the model layer, orchestration, vector infrastructure, compliance scaffolding, and a decent chunk of the integration layer. Call it 60-70% of the technical surface area. This is the commodity layer, and it is getting commoditized faster than most vendors in the space want to admit. If your pitch deck says “we built a proprietary LLM” or “our secret sauce is our vector database,” those claims are increasingly unpersuasive to sophisticated investors who understand what’s available off the shelf.

The custom 30-40%: where health systems actually differ

Here’s where things get complicated and interesting. The remaining 30-40% of the stack, concentrated primarily in the workflow and rules layer and in the integration specifics, is where healthcare organizations are fundamentally different from each other in ways that matter enormously for agent performance.

Start with EHR variability. Epic, Oracle Health (formerly Cerner), Meditech, and a few others are the dominant EHR vendors, but “running Epic” doesn’t mean two health systems have anything close to the same data model. Epic is famously configurable, which is both its commercial strength and a deployment nightmare for anyone building on top of it. Two large academic medical centers running Epic Cogito can have CDMs (clinical data models) so divergent that a model trained or configured on one system will fail in meaningful ways on the other. Custom build types, non-standard flowsheet rows, local formularies, home-grown order sets, legacy data migration artifacts, none of this is standardized. This is not a solvable problem through better APIs alone. It requires human investigation.

Beyond EHR variability, the actual clinical and administrative workflows at any given health system are a product of years of organizational history, regulatory responses, payer contract specifics, and individual human workarounds that never got cleaned up. The McKinsey number on US healthcare administrative costs, roughly $350B annually, isn’t just a market opportunity number, it’s also a signal of how many people are currently doing work that could theoretically be automated, but only if you understand exactly what they’re doing and why. A prior authorization workflow at a large integrated delivery network might involve eight different handoff points, two different payer portals that use incompatible authentication methods, an internal approval queue that runs on a SharePoint list from 2017, and a set of clinical criteria that the CMO updated last quarter but that nobody has fully communicated to the coding team. An agent built on generic prior auth logic will get about 60% of the way there. The last 40% requires encoding the specific logic that applies at that organization.

Clinical variation adds another layer. Even within standardized workflows like sepsis protocols or medication reconciliation, there is legitimate clinical judgment variation that agents must handle correctly or defer appropriately. The difference between a safe AI agent in a clinical workflow and an unsafe one is not primarily model capability, it’s whether the workflow layer correctly encodes when to act versus when to escalate, and that boundary is different at different organizations, different care settings, and different patient populations. Getting this wrong has real consequences. The FDA’s evolving framework for AI/ML-based software as a medical device (SaMD) and the recent executive order guidance on clinical AI make clear that regulatory scrutiny on exactly this question is increasing.

There’s also the integration-specific custom layer that goes beyond what FHIR standardizes. Lab information systems, pharmacy systems, scheduling systems, billing and RCM platforms, payer portals, state Medicaid management information systems (MMIS), prior auth portals that use screen scraping because they have no APIs, document management systems running on file shares. The full technology landscape inside a typical health system involves dozens of these point solutions, many of which have no standard API, some of which are actively hostile to programmatic access, and all of which need to talk to each other through an AI agent that is supposed to complete a coherent multi-step task. This cannot be solved generically. Someone has to map it, and that someone needs to be on-site.

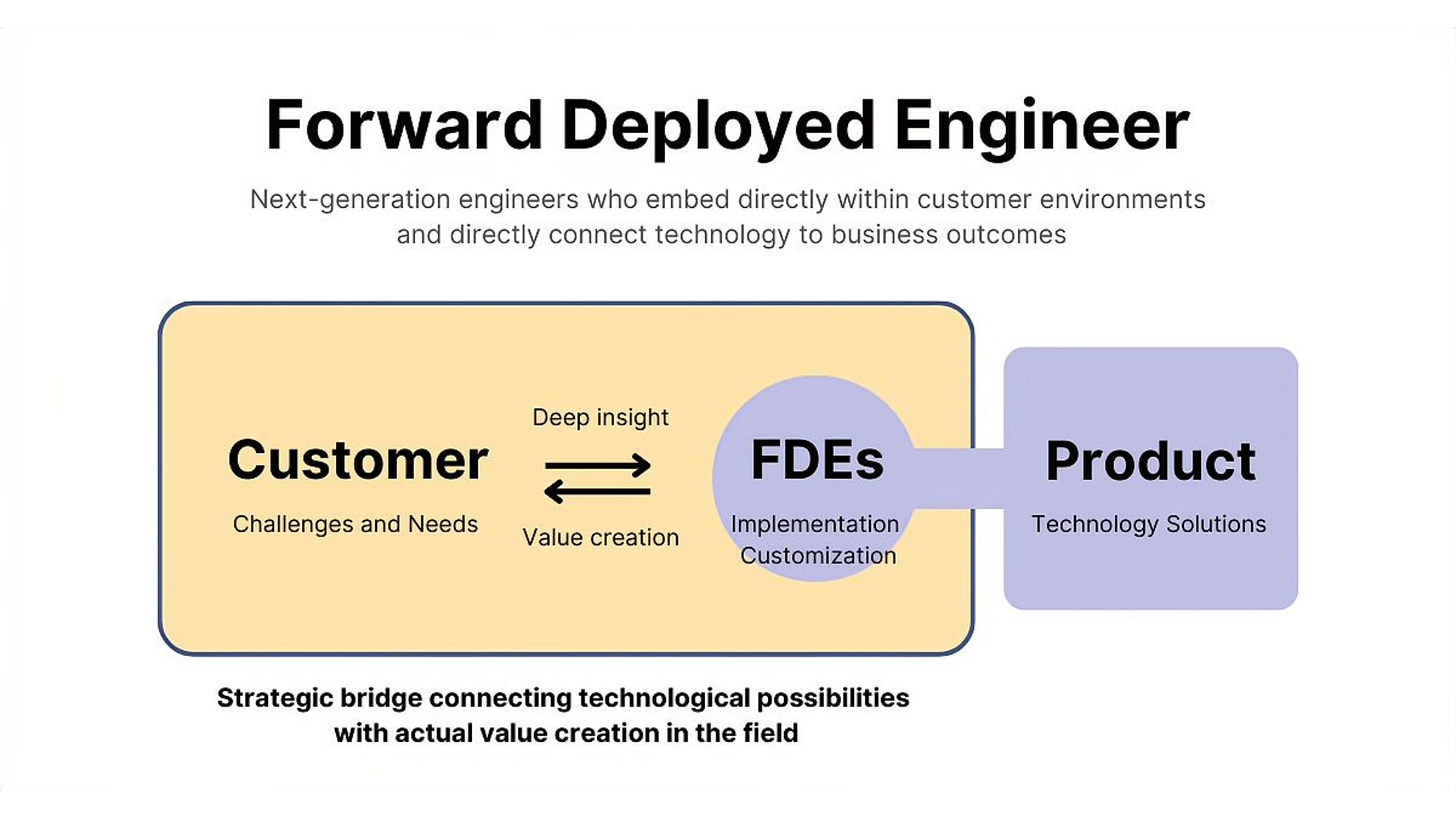

The Palantir FDE model and why it translates

Palantir Technologies built its business on a model that was, at the time, considered strange and possibly unscalable: instead of selling software and letting customers implement it, they embedded engineers inside client organizations for months or years to understand the data environment, map the workflows, and build the integrations and logic layers that made the platform actually useful. They called these people Forward Deployed Engineers, and the approach originated at places like the CIA and DoD where the stakes were high enough that failing to understand the operational context would mean the software just didn’t work.

The FDE model got a lot of criticism from traditional SaaS investors because it looks expensive and it doesn’t scale the way a pure software business does. Revenue per employee metrics suffer. The argument in favor of it was always that in sufficiently complex environments with sufficiently high stakes, you cannot separate the software from the domain knowledge required to configure it correctly, and trying to do so via documentation, onboarding calls, and customer success handholding is how you end up with shelfware.

This translates to healthcare AI agent deployment with remarkable fidelity. The complexity argument applies directly. Health systems are not going to figure out how to correctly configure an AI agent for complex clinical workflows from a 200-page implementation guide and a Slack channel with a CSM. The stakes argument also applies, because errors in clinical or even administrative workflows have real consequences, regulatory, financial, and patient safety. And the data environment argument applies most directly of all, because the workflow and data complexity described in the previous section is precisely the kind of thing that only becomes visible when someone is in the room.

What forward deployed engineering looks like in a healthcare AI agent deployment is roughly this: a team of two to four engineers and at least one clinical or operational domain expert is embedded at the health system for anywhere from six weeks to six months. Their job in the first phase is not to build anything. It’s to observe and document. They sit with coders, with billing staff, with care coordinators, with prior auth specialists. They pull actual workflow data from the EHR and the ticketing systems and the shared drives. They find the SharePoint lists and the Excel macros and the email threads that are doing load-bearing work in processes that the org chart says are automated. They map the decision trees that experienced staff use implicitly without ever having written them down.

In the second phase, they translate that knowledge into the workflow and rules layer of the agent stack. This is where the custom 30-40% gets built. Integration adapters for non-standard endpoints. Decision logic trees that encode the real approval criteria, not the theoretical ones. Escalation rules that match how the organization actually wants to handle exceptions. Validation checks that catch the kinds of errors specific to that health system’s data quality issues. This is slow, skilled work. It is also the work that determines whether the agent actually performs or whether it sits at 60% accuracy and never gets used in production.

Companies doing this well in 2024 include some of the better-known clinical AI platforms that have been around long enough to have built real deployment infrastructure, and a newer cohort of agent-focused startups that have explicitly adopted the FDE model. The ones that haven’t are often the ones with the better press coverage and the worse enterprise deployment track records.

Economics of the FDE approach for startups and health systems

The honest conversation about the FDE model is that it’s expensive and the economics are genuinely hard to make work at early stages. A forward deployed engineer team for a six-month health system engagement might cost $600K to $900K in fully-loaded costs before you’ve closed a software contract. For a Series A startup, that’s a painful burn rate on a single customer. This is why so many companies try to skip it, and why so many pilots fail to convert to enterprise deployments.

The way the math works for the FDE model to be viable is through a combination of higher ACV (annual contract values), reusability of deployment artifacts, and time compression as the team builds institutional knowledge about the health system type. On ACV, healthcare AI agent deployments that include real workflow customization and integration work should command $500K to $2M+ annually from large health systems, not the $50K to $150K SaaS pricing that gets thrown around for lighter-weight tools. The organizations that have the most complex problems and the most to gain from agent automation also have the budget and the willingness to pay for a high-quality deployment. The pitch shifts from “here’s our software” to “here’s what our team will accomplish for your organization in the first 12 months,” which is a services-plus-software model that most pure SaaS investors still misunderstand.

On reusability, this is where the FDE model starts to get more economically interesting over time. Every EHR configuration, every payer portal integration, every workflow mapping effort produces artifacts that are partially reusable at the next similar customer. An FDE team that has deployed inside five health systems running Epic in the northeast US has built up a library of Epic configuration patterns, common workflow variations, integration adapters, and tested decision logic that meaningfully reduces the time required to deploy at the sixth similar health system. The marginal cost of deployment decreases over time even as the quality of deployment stays high or improves. This is how Palantir’s unit economics eventually improved despite the high upfront cost model.

For health systems as buyers, the FDE model is actually better aligned with how they want to procure technology even if they don’t always articulate it that way. CIOs and CMIOs at large health systems are deeply skeptical of point solution vendors who promise self-serve deployment. They’ve been burned too many times. The offer of an embedded expert team that will spend real time understanding their specific environment before building anything is a more credible pitch than a demo showing a generic prior auth workflow that looks nothing like how they actually process prior auths. The total cost of a well-executed FDE-model deployment is often lower than a failed self-serve deployment followed by a year of remediation work and eventual contract termination.

The investor tension around this model is worth naming directly. SaaS multiples are driven by revenue growth and gross margin. Services revenue gets punished in public market valuations and often in venture valuation conversations too. Companies that have built real FDE capability often try to hide it behind “professional services” line items or undercharge for it in order to keep their software revenue metrics clean. This is strategically wrong and often leads to the FDE capability being underfunded relative to what it needs to be. The better frame for investors is that FDE is a moat-building activity, not a services business. The workflow knowledge and deployment artifacts built through FDE engagements are proprietary data assets that competitors cannot easily replicate, and they compound over time in ways that pure software does not.

What this means for investors

For anyone allocating capital to healthcare AI agent companies, the standardization/customization framework has some direct implications for due diligence and portfolio construction.

First, be suspicious of companies whose entire technical differentiation story lives in the commodity layer. If the pitch is “we have the best LLM fine-tuned for healthcare” or “our vector database is optimized for clinical notes,” those are real technical achievements but they are not durable moats. The foundation model providers and infrastructure vendors will eat most of that differentiation within 12-24 months. The durable moat in healthcare AI agents lives in the workflow layer, in the proprietary knowledge of how specific care settings and organizations actually operate, in the integration adapters and decision logic that have been built and tested and refined over hundreds of real deployments.

Second, look for evidence of real deployment at real health systems at real scale. This sounds obvious but in an environment where demo-stage companies are raising at Series B valuations based on pilot announcements and press releases, it requires active effort. Ask for production deployment metrics, not pilot metrics. Ask how many patients or encounters the agent has processed in a non-sandboxed environment. Ask what the false positive or escalation rate is. Ask how many full-time people from the vendor are embedded at each customer. Ask what the P1 incident rate is. These questions separate companies with working deployments from companies with impressive demos.

Third, the FDE model is a positive signal, not a negative one, even if it makes the unit economics look worse in a model. A company that has built real FDE capability and is using it to generate proprietary workflow knowledge at enterprise customers is building something that is genuinely hard to replicate. The cost structure is real, but so is the moat. A company that has grown to $20M ARR through FDE-model deployments at 15 health systems has a data and knowledge asset that a competitor with a cleaner SaaS model and $30M ARR through 200 small customers probably does not.

Fourth, think carefully about the category structure of healthcare AI agent companies. There are horizontal players trying to build general-purpose agent infrastructure for healthcare, and there are vertical players building for specific workflows like prior auth, clinical documentation, coding, or care coordination. The standardization/customization tradeoff argues somewhat in favor of vertical focus, at least at early stages, because deep workflow knowledge in a specific domain is more achievable and more defensible than trying to map workflows across every healthcare use case simultaneously. The horizontal players that win will probably be the ones that built very deep vertical expertise first and then expanded, not the ones that started with generic infrastructure and tried to add vertical depth later.

Fifth, the companies most at risk in this landscape are the mid-tier: too expensive to deploy rapidly at SMB health systems, not deep enough in workflow expertise to win enterprise deployments against vendors who have been doing FDE-style work for years. The dumbbell structure of the market (lightweight self-serve tools for small practices and deeply embedded solutions for large health systems) is going to squeeze the middle.

Where this is all going

The trajectory here is not that FDE goes away as agents get smarter. The trajectory is that the cognitive burden of the FDE engagement shifts. Two years ago, the forward deployed engineer was spending most of their time on raw integration work, writing Python scripts to parse HL7 feeds and building one-off adapters for payer portals. That work is getting easier faster than almost anything else in the stack, as the ecosystem of health IT integrations, FHIR compliance, and managed API platforms matures. A non-trivial portion of the integration layer will be handled by commodity tooling within 24 months.

What won’t get commoditized is the workflow observation and encoding work. You cannot send a model to watch someone work and capture the implicit decision logic that experienced healthcare workers carry in their heads. That knowledge elicitation work is fundamentally a human process, requiring trust, domain vocabulary, patience, and the ability to ask the right follow-up questions when a nurse says “oh we just know when to flag it.” The value of the FDE team is shifting from integration engineering toward something closer to workflow anthropology plus rapid prototyping, and the profiles of the best people to do this work are also shifting accordingly.

The interesting longer-term question is whether the workflow knowledge accumulated through FDE deployments can itself become training data for models that eventually reduce the customization burden. There are early signs of this: companies that have done enough deployments to have a large corpus of labeled healthcare workflow examples are starting to fine-tune models on that data in ways that reduce the time required to onboard a new similar organization. This is a legitimate form of compounding moat, workflow knowledge encoded in deployment artifacts, used to train better models, which reduce deployment cost, which allows more deployments, which generates more workflow knowledge. It’s a flywheel, and the companies that are already executing on it are probably further along in building durable competitive advantages than their current revenue figures suggest.

The final point worth making is about timing. The window where a company can acquire deep workflow knowledge in a specific healthcare AI agent category without facing well-resourced competition is probably two to three years, not five to ten. The big EHR vendors, the large RCM companies, and a few well-capitalized health AI incumbents are all moving toward agent-based products. They have existing health system relationships and embedded sales motion advantages that new entrants don’t. The moat that a focused, FDE-model startup can build before those players are fully in the market is real but it has a time limit. The companies that will still be relevant in ten years are the ones deploying real agents into real workflows right now, not the ones waiting for the infrastructure to mature further or for the regulatory environment to clarify. That clarity is coming, but it rewards those who have already done the deployment work, not those who are watching from the sidelines.