Unlocking EHR Data: The Legal and Contractual Path to Screen Scraping for Real-Time Analytics

In the battle for real-time interoperability, the healthcare industry has long wrestled with the barriers posed by closed EHR ecosystems. With major players like PointClickCare (PCC) asserting strict contractual control over data access, organizations looking to extract and utilize electronic health record (EHR) data in real time often face an uphill legal and technical battle.

But what if courts were to allow EHR screen scraping as a viable alternative to direct API-based access? What minimal provider agreements and contracts would be required to ensure legal defensibility while achieving a level of real-time data parity with API-based solutions?

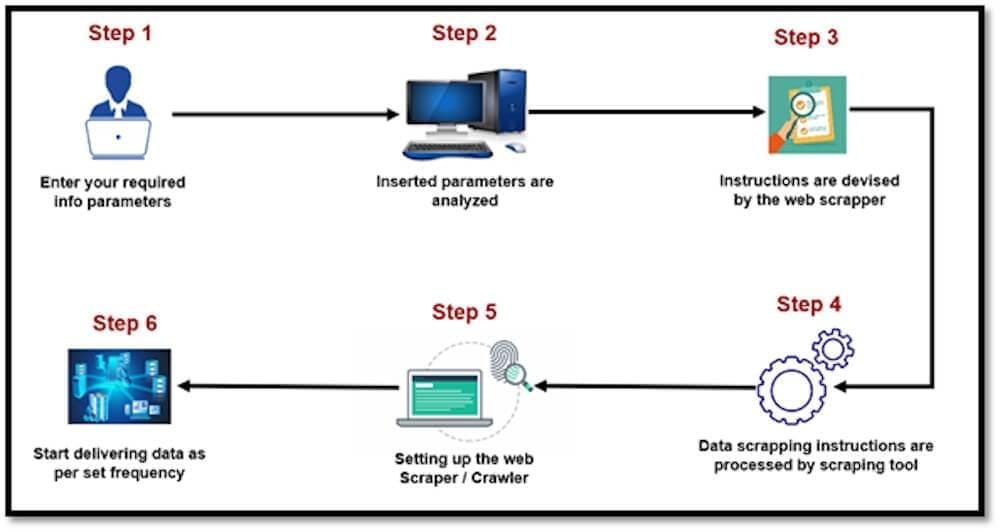

Screen Scraping: The Last Resort for Real-Time Data Access

EHR vendors argue that their platforms are proprietary and that external scraping of their user interfaces violates terms of service, intellectual property rights, and data security policies. However, courts have increasingly ruled that screen scraping may be permissible when users have a legitimate right to access and use the data.

In hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn (2022), the U.S. courts ruled that screen scraping of publicly available LinkedIn data did not violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). While healthcare data is more complex—governed by HIPAA, the 21st Century Cures Act, and state laws—there is a legal precedent suggesting that providers may assert a right to access and use their own patient data, even via nontraditional means.

Key Legal and Contractual Requirements for Permissible Screen Scraping

For courts to recognize and permit EHR screen scraping as a lawful real-time data extraction method, healthcare organizations would need a minimal set of agreements and contracts ensuring compliance with:

1. Provider-EHR Vendor Agreements

Most EHR vendors include anti-scraping clauses in their contracts, which means providers need to explicitly negotiate:

Data Ownership Clauses: Ensuring that the provider, not the EHR vendor, retains full rights to their patient data.

Third-Party Access Rights: A provision allowing the provider to authorize external entities to access and extract data from the system.

Restrictions on Blocking Access: Prohibiting the vendor from using technical measures (CAPTCHAs, rate limiting, obfuscation) to prevent provider-authorized scraping.

2. Provider-Third Party Data Access Agreements

If a provider partners with a third-party data analytics firm or health IT vendor to perform screen scraping, they must establish:

Business Associate Agreements (BAAs): Required under HIPAA to govern PHI handling.

Data Use and Security Agreements (DUSA): Defining permitted use cases and security measures to prevent breaches.

Liability and Indemnification Clauses: Addressing potential risks if scraping causes system performance issues or unauthorized data exposure.

3. Patient Consent and Terms of Use Updates

Patients may need to explicitly consent to their data being accessed via scraping-based mechanisms if this differs from standard API-based interoperability methods. This can be addressed through:

Revised Notice of Privacy Practices (NPPs): Informing patients that real-time data extraction may occur via automated methods.

Opt-In/Opt-Out Mechanisms: Giving patients control over how their data is accessed.

4. Compliance With Information Blocking Rules

Under the 21st Century Cures Act, EHR vendors cannot block provider access to patient data unless there is a legitimate security concern. However, vendors often claim that screen scraping is a security risk, potentially justifying blocking mechanisms.

To counteract this, providers should:

Document security safeguards in their scraping approach.

Demonstrate that scraping is necessary due to the vendor’s failure to provide timely or affordable API-based access.

Leverage ONC complaints if an EHR vendor unfairly restricts provider data access.

The Future: Can Screen Scraping Become a Standard Data Access Model?

If courts uphold provider rights to screen scraping, this could reshape the balance of power in healthcare interoperability. Instead of being locked into proprietary vendor ecosystems, hospitals and physician groups could extract real-time data without dependence on vendor-controlled APIs.

However, the battle will likely be fought at the intersection of contract law, regulatory enforcement, and evolving case law. Healthcare providers looking to challenge restrictive EHR contracts must build legal, compliance, and technical safeguards—ensuring their right to real-time access is both defensible and sustainable.

In the end, the question isn’t whether screen scraping is an ideal solution—it’s whether providers can establish a legally and contractually sound right to use it when no better alternative exists.