When CMS Moves Markets: The Hidden Architecture of Health Tech Commercialization

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this essay are solely my own and do not reflect the positions, strategies, or opinions of my employer or any affiliated organizations.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract

Introduction

The Mechanics of Coverage Determination

The Reimbursement Chasm

When CMS Moves Markets

The Venture Calculus

The Clinical Evidence Paradox

Strategic Implications for Founders

Looking Forward

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

• CMS coverage determinations function as powerful market validation mechanisms that extend far beyond simple reimbursement decisions

• The agency’s decisions create cascading effects across commercial payers, venture capital, and product development timelines

• Companies face a circular dependency: clinical evidence requirements demand scale that requires reimbursement that requires evidence

• Strategic founders increasingly treat CMS engagement as a market creation tool rather than a post-commercialization milestone

• Understanding coverage pathways has become essential for de-risking health tech ventures targeting Medicare populations

When CMS Moves Markets: The Hidden Architecture of Health Tech Commercialization

There is a peculiar asymmetry in healthcare entrepreneurship that rarely gets discussed at demo days or in pitch decks. A company can have exceptional clinical data, a technically sophisticated product, enthusiastic early adopters, and a compelling unit economics story, yet find itself stalled at ten or fifteen million in revenue, unable to break through to meaningful scale. The pattern repeats itself across therapeutic areas and technology categories with remarkable consistency. What these companies eventually discover, often after burning through significant runway, is that they have been building toward the wrong inflection point. The real gate is not product market fit in the traditional sense, nor is it achieving some arbitrary quality metric or securing a partnership with a prestigious health system. The gate is a coverage determination from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and everything in their go-to-market strategy should have been reverse engineered from that reality.

This is not a story about regulatory capture or the frustrations of dealing with government bureaucracy, though both elements exist. This is about something more fundamental: CMS has become the de facto arbiter of what constitutes a legitimate healthcare innovation in the American market. The agency’s coverage decisions carry an authority that transcends their direct financial impact, creating ripple effects that determine venture fundability, commercial payer behavior, physician adoption patterns, and even the technical roadmaps of competing solutions. For founders building in health tech, understanding this dynamic is not ancillary knowledge. It is the architecture upon which successful commercialization strategies must be constructed.

The Mechanics of Coverage Determination

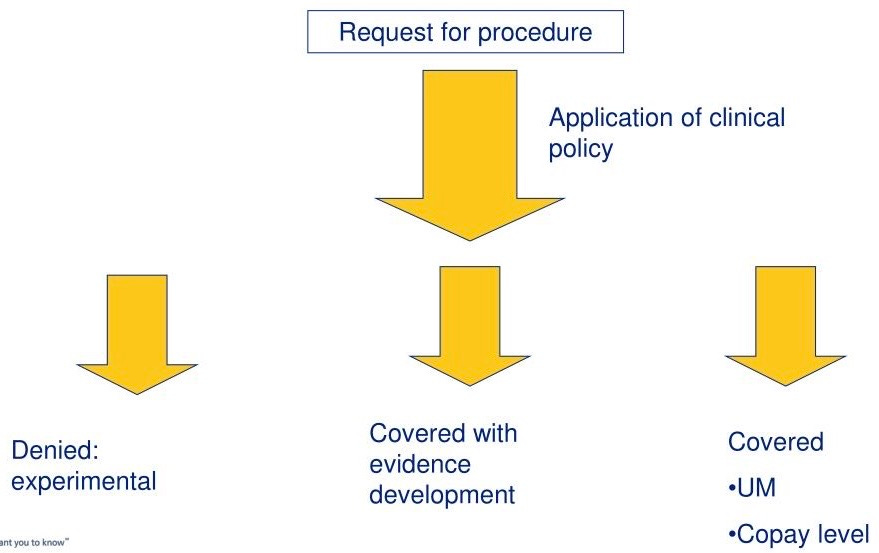

To understand why CMS coverage determinations function as market catalysts, one must first appreciate the mechanism itself. Medicare coverage is not a binary switch but rather a complex landscape of pathways, each with different evidentiary requirements, timelines, and strategic implications. The most straightforward route is through existing coding and payment structures, where an innovation fits neatly into established categories. This path offers speed but typically comes with pricing constraints and the risk of being commoditized alongside inferior alternatives. For truly novel technologies, the National Coverage Determination process represents the gold standard, a comprehensive review that can take eighteen to twenty-four months but results in nationwide coverage policy. Local Coverage Determinations offer regional entry points, allowing companies to build evidence and momentum in specific markets before pursuing broader coverage.

Then there is the Coverage with Evidence Development pathway, which emerged as CMS’s answer to the chicken-and-egg problem of innovative technologies that show promise but lack the level of evidence traditionally required for coverage. Under CED, Medicare will reimburse for a technology while additional data is collected through registries or clinical trials. This sounds elegant in theory, but in practice it creates its own complications. The requirements for CED are often ambiguous until late in the process, the administrative burden of maintaining qualifying registries can be substantial, and the provisional nature of coverage makes some providers hesitant to invest in adoption.

What makes these pathways particularly relevant to entrepreneurs is not just their direct impact on revenue, but how they shape every other stakeholder’s calculus. When CMS signals that a technology merits serious consideration through any of these mechanisms, it validates the underlying clinical and economic premise in ways that no amount of venture capital or commercial success can replicate. The agency is understood to be cautious, evidence-focused, and insulated from the hype cycles that characterize consumer technology. If CMS is paying attention, serious people take note.

The Reimbursement Chasm

The challenge for early-stage health tech companies is that CMS coverage becomes most valuable precisely at the stage when it is hardest to achieve. Consider the typical trajectory of a diagnostic or therapeutic technology. In the first few years, the company is focused on product development, initial clinical validation, and securing regulatory clearance or approval. Funding comes from angels, seed investors, and perhaps a Series A round predicated on hitting technical and regulatory milestones. The assumption, often implicit, is that reimbursement will follow once the product is proven and on the market.

This assumption is dangerously naive. By the time a company has FDA clearance and begins commercial sales, it enters what might be called the reimbursement chasm, a period where revenue growth is constrained by the absence of consistent coverage, but the evidence required for coverage requires scale that revenue constraints make difficult to achieve. The company can often secure some early adopters, academic medical centers interested in the technology or health systems willing to pilot innovative solutions. But these initial customers rarely provide sufficient volume to generate the real-world evidence that payers demand, particularly for technologies where outcomes play out over months or years rather than days or weeks.

The financial implications are severe. A company might project eighteen months of runway to reach a Series B milestone, only to find that without broader reimbursement, customer acquisition costs are far higher than modeled, sales cycles stretch from six months to eighteen, and the contracted revenue never materializes at the assumed rate. The natural response is to raise more capital, but here the company encounters another dimension of the coverage problem. Sophisticated healthcare investors know this pattern intimately, and they discount valuations and impose term sheet provisions accordingly. The company that raised its Series A at a strong valuation pre-commercialization may find its Series B is effectively a down round once the reimbursement reality becomes apparent.

When CMS Moves Markets

The counterexample is instructive. When CMS issues a positive National Coverage Determination or expands existing coverage to include a new technology category, the market effects are immediate and multifaceted. The most obvious impact is on revenue, as Medicare-eligible patients suddenly become economically viable customers. For technologies targeting older populations or chronic conditions prevalent in that demographic, this can mean the addressable market increases by fifty to seventy percent overnight. But the downstream effects often matter more than the direct revenue impact.

Commercial payers, despite their frequent protestations of independence, tend to follow Medicare’s lead on coverage decisions. The reasons are partly practical: CMS conducts rigorous technology assessments that commercial payers can leverage rather than duplicating. But there is also a deeper dynamic at play. Medicare coverage creates a political and public relations baseline that makes it difficult for commercial payers to deny coverage for the same indication. Patient advocacy groups will point to Medicare coverage as evidence of medical necessity, physicians will question why their commercially insured patients cannot access the same standard of care, and employers who fund self-insured plans will ask their benefits consultants why they are paying for alternatives that Medicare deems inferior.

The venture capital implications are equally significant. A positive coverage determination transforms a company’s risk profile in ways that extend well beyond the revenue impact. Investors know that follow-on funding will be easier to secure, that strategic acquirers will be more interested, and that the company has cleared the single biggest non-clinical hurdle to achieving scale. More subtly, coverage provides validation of the company’s scientific and clinical thesis that matters to investors who may lack deep domain expertise. A venture partner evaluating a diagnostic startup in an unfamiliar disease area faces genuine uncertainty about whether the clinical value proposition is real or just sophisticated marketing. When CMS concludes that the evidence supports coverage, it resolves that uncertainty in a way that the company’s own claims never could.

This dynamic has created an interesting feedback loop in health tech venture capital. Firms with dedicated healthcare teams have become increasingly sophisticated about coverage pathways and often require portfolio companies to develop reimbursement strategies as early as the Series A stage. Some investors will not lead rounds for companies targeting Medicare populations unless there is a credible path to coverage within the fund’s return horizon. This investor sophistication has in turn raised the bar for founders, who now need to demonstrate fluency with coverage policy to secure institutional funding.

The Clinical Evidence Paradox

The challenge that bedevils many health tech companies is what might be called the clinical evidence paradox. To secure coverage, particularly through an NCD, companies need robust clinical evidence including randomized controlled trials demonstrating clinical utility and ideally health economic data showing cost effectiveness. But conducting these trials requires capital and time, often millions of dollars and multiple years. Early-stage companies rarely have the resources to fund such studies before they have revenue, yet they cannot achieve meaningful revenue without the coverage that requires the evidence. The circle is vicious and has destroyed many promising companies.

There are escape routes, but each comes with tradeoffs. Some companies pursue coverage through existing codes, accepting lower reimbursement rates and imperfect fit rather than waiting for ideal coverage. This can work for technologies with low marginal costs and where adequate payment exists within current structures, but it leaves value on the table and creates competitive vulnerability. Other companies seek partnerships with established healthcare companies who have the resources to fund clinical trials and the relationships to navigate coverage pathways. These partnerships can be life-saving, but they typically involve giving up significant economics and often some degree of strategic control.

The Coverage with Evidence Development pathway was designed to address this paradox, allowing companies to generate real-world evidence while receiving payment. But CED comes with its own challenges. The administrative requirements can be substantial, particularly for smaller companies without dedicated reimbursement teams. The provisional nature of CED coverage creates uncertainty for providers and patients. And most significantly, CED typically requires that companies have already generated substantial evidence to even qualify, meaning it addresses the evidence generation problem but not the cold start problem of funding initial trials.

The most successful companies tend to take a portfolio approach to evidence generation. They combine pragmatic early revenue through existing coverage pathways with strategic investments in the clinical evidence that will support broader coverage. They prioritize trial designs that serve multiple purposes, satisfying regulatory requirements while also generating data relevant to payers. They cultivate relationships with CMS staff years before submitting formal coverage requests, using informal conversations to calibrate their evidence strategy. And they recognize that evidence generation is not something to be handled by the clinical team in isolation, but rather a strategic priority that should shape product development, market selection, and capital allocation decisions.

Strategic Implications for Founders

For founders building health tech companies, these dynamics suggest several strategic principles. The first is the importance of early clarity about the coverage pathway. Too many companies treat reimbursement as something to figure out after product development and regulatory clearance, a mindset that made sense in an earlier era but is increasingly untenable. The companies that scale effectively tend to identify their likely coverage pathway during the seed stage and reverse engineer their development plans accordingly. If the technology will require an NCD, that implies certain decisions about clinical trial design, patient population, endpoints, and commercialization timing. If the technology can fit within existing payment structures, that suggests different priorities around pricing, positioning, and go-to-market strategy.

The second principle is that engagement with CMS should begin far earlier than most founders anticipate. The agency is more accessible than many entrepreneurs realize, and informal conversations during the development process can provide invaluable guidance about evidentiary expectations and coverage considerations. Waiting until a product is on the market and revenue is stalling to begin these conversations is a mistake. By that point, the company may have made product design or clinical development decisions that are difficult to reverse but that create unnecessary hurdles to coverage.

Third, founders should think carefully about their initial market selection through a coverage lens. The temptation is to pursue the largest addressable market or the customers who are easiest to reach, but this can be strategically misguided if it does not build toward a coverage strategy. Sometimes the optimal early market is the one that will generate the evidence and precedent most relevant to eventual CMS coverage, even if it is not the largest or most accessible segment. A diagnostic company might focus on specialty academic centers that can contribute to registries, or a therapeutic technology might prioritize indications where outcomes are measurable over shorter time horizons.

Fourth, capital allocation should explicitly account for evidence generation costs and timelines. Many health tech companies under-allocate to clinical and health economic studies, treating them as unfortunate necessities rather than strategic investments. This is a mistake. The evidence is not separate from the product; it is part of what the company is building. A diagnostic technology without the evidence to support coverage is not a complete product, regardless of how sophisticated the underlying science. Founders should model their cash runway not to product launch but to evidence sufficiency for coverage, and they should be willing to slow other aspects of development to prioritize evidence generation if necessary.

Fifth, companies should cultivate coverage expertise internally rather than relying solely on consultants. The consulting firms that specialize in reimbursement strategy provide valuable services, but there is a risk in outsourcing strategic thinking about coverage to external advisors. The founders and executive team need to deeply understand coverage pathways, evidentiary requirements, and payer dynamics. This knowledge should inform product development decisions, partnership negotiations, and capital allocation. Consultants can provide tactical support and relationships, but the strategy must be owned internally.

Looking Forward

The role of CMS as market catalyst raises important questions about the future of health tech innovation. On one hand, the agency’s rigorous approach to evidence evaluation provides important protection for patients and stewardship of public resources. Medicare beneficiaries are often elderly and vulnerable, and the program has a responsibility to ensure that covered technologies provide genuine clinical value. The evidentiary bar that CMS maintains likely prevents the adoption of some technologies that would prove to be ineffective or harmful, even if it also slows the diffusion of beneficial innovations.

On the other hand, the outsized influence of CMS coverage decisions on broader market dynamics creates real inefficiencies. Technologies that would be valuable for commercially insured populations may never reach the market because the capital requirements to satisfy CMS evidentiary standards are prohibitive for early-stage companies. The focus on randomized controlled trials, while scientifically rigorous, may be poorly suited to evaluating certain types of technologies, particularly those involving software or care delivery models where blinding is impossible and context matters enormously. And the long timelines for coverage determinations are fundamentally mismatched with the pace of innovation in digital health and artificial intelligence.

There are signs that CMS is evolving its approach to coverage in recognition of these challenges. The agency has shown greater interest in real-world evidence, particularly for technologies where traditional RCTs are impractical. The expansion of Coverage with Evidence Development pathways suggests openness to iterative approaches that balance access with evidence generation. And recent proposals around adaptive coverage would allow Medicare to cover emerging technologies provisionally while collecting data, with payment amounts potentially adjusting based on real-world performance.

For entrepreneurs, these policy developments create both opportunities and risks. The shift toward real-world evidence and adaptive approaches could lower barriers to coverage for innovative technologies, particularly those involving software and data. But it also places greater emphasis on data infrastructure and analytical capabilities. Companies will need to build robust systems for capturing, analyzing, and reporting real-world outcomes data, capabilities that require investment and technical sophistication.

The increased CMS focus on health equity also has strategic implications. Coverage determinations are increasingly considering whether technologies exacerbate or ameliorate disparities in care delivery and outcomes. Technologies that are only accessible to certain patient populations or that perform differently across demographic groups may face coverage challenges. For founders, this means that equity considerations need to be embedded in product development and clinical validation from the beginning, not addressed as an afterthought when coverage questions arise.

Conclusion

The central reality of health tech entrepreneurship is that CMS coverage determinations are not merely reimbursement decisions but rather inflection points that fundamentally reshape market dynamics. A positive coverage determination validates clinical value propositions, catalyzes commercial payer coverage, attracts venture capital, and accelerates adoption in ways that compound over time. The companies that achieve scale are almost always those that recognized this reality early and built their entire commercialization strategy around securing coverage. Those that treat reimbursement as something to figure out after product development typically find themselves trapped in the reimbursement chasm, burning cash while trying to generate the evidence needed for coverage without the revenue to fund evidence generation.

For founders building health tech companies today, particularly those targeting conditions prevalent in Medicare populations, coverage strategy should be as central to the business plan as product development or regulatory approval. This means engaging with CMS early, designing clinical development programs that serve both regulatory and reimbursement objectives, and making capital allocation decisions that prioritize evidence generation. It means being realistic about timelines and capital requirements, recognizing that the path from FDA clearance to meaningful revenue may be longer and more expensive than venture analogies from other sectors would suggest.

The companies that successfully navigate coverage pathways create enormous value, both for their investors and for the patients who gain access to beneficial technologies. But success requires a level of strategic sophistication about healthcare payment and policy that many founders lack when they begin their entrepreneurial journeys. The good news is that this knowledge is accessible to those willing to invest the time to understand coverage mechanisms and to build relationships within the payer community. CMS staff are generally willing to engage with companies developing innovative technologies, and the agency has made efforts to provide greater transparency about coverage processes and evidentiary expectations. The resources exist for founders who are willing to do the work.

Ultimately, the outsized influence of CMS coverage determinations on health tech markets reflects deeper truths about healthcare as an industry. Unlike consumer technology, where users directly pay for products and can evaluate value for themselves, healthcare involves complex principal-agent relationships, information asymmetries, and third-party payment. In this context, coverage decisions by large payers serve an important coordinating function, providing signal about clinical value that helps align incentives across providers, patients, and other payers. CMS occupies a unique position within this ecosystem by virtue of its scale, analytical capabilities, and insulation from short-term commercial pressures. When the agency concludes that evidence supports coverage, it resolves uncertainty in ways that ripple across the entire market.

For entrepreneurs willing to engage deeply with coverage dynamics, this creates opportunities to build companies that are not just scientifically innovative but also strategically sophisticated about commercialization pathways. These companies understand that their product is not just the device or software or diagnostic test, but rather a combination of technology, clinical evidence, and reimbursement strategy. They recognize that achieving scale in healthcare requires patience and capital, but that the returns to companies that successfully navigate these challenges can be substantial. Most importantly, they approach coverage not as an obstacle to be overcome but as an integral part of how value is created and captured in healthcare markets.

If you are interested in joining my generalist healthcare angel syndicate, reach out to treyrawles@gmail.com or send me a DM. We don’t take a carry and defer annual fees for six months so investors can decide if they see value before joining officially. Accredited investors only.

I resonate with your core insight about CMS acting as a market creation lever, though it makes me ponder if such a centralized gatekeeper, despite its validation power, might trully stifle disruptive health tech solutions that initially lack the scale for robust clinical evidenve.